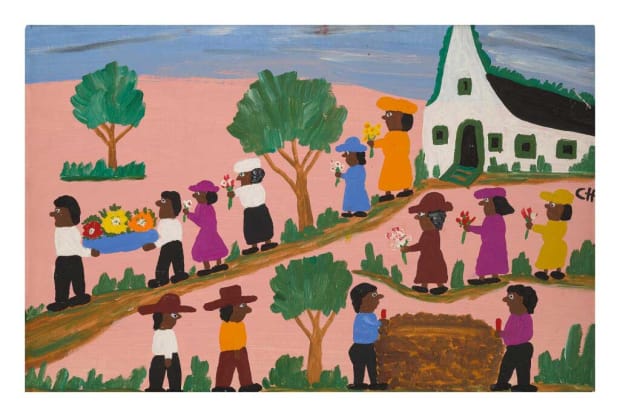

#SelfTaught #Artist #Clementine #Hunter #Painted #Bold #Colorful #Life #Plantation

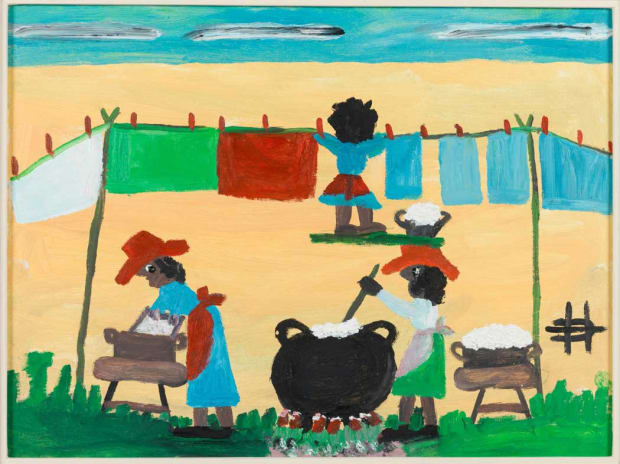

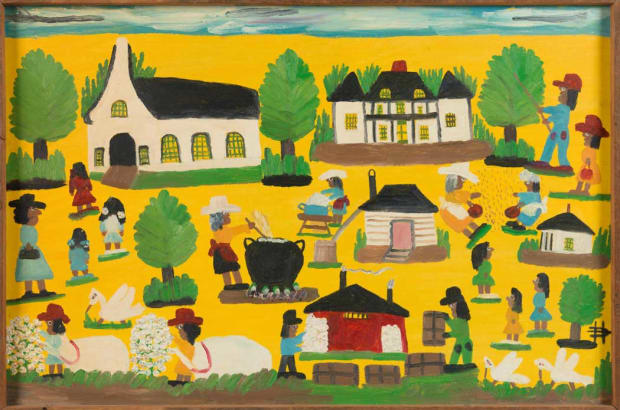

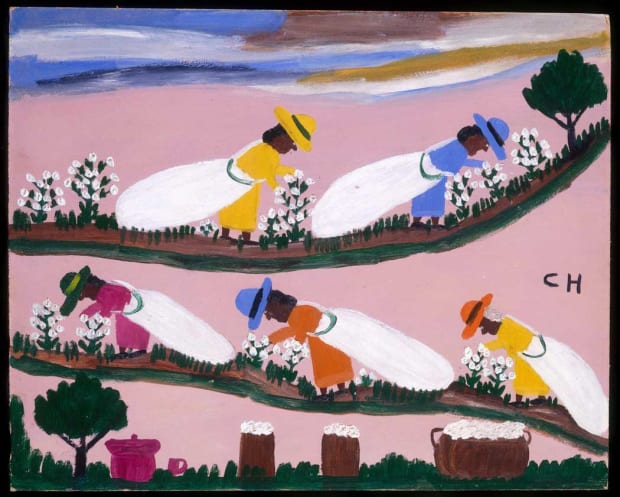

Born twenty years after the Civil War, Hunter painted Black life in the South, from working in the field, to church on Sundays, and laundry on the line.

A Louisiana farm laborer, Clementine Hunter could neither read nor write. It wasn’t until she was in her mid-50s, that she taught herself to paint. And yet, in 1955, Hunter became the first Black artist to have a solo show at the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Before she died in 1988, she had received an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree, been invited to Washington, D.C., by President Jimmy Carter and become a household name in her home state — where October 1 is now “Clementine Hunter Day.” In 2013, an opera about her, Zinnias: the Life of Clementine Hunter, was performed at Montclair State University in New Jersey.

Courtesy Schlesinger Library, Harvard University

Hunter was born in 1886 (or 1887, it’s unclear) on Louisiana’s notorious Hidden Hill Plantation, the harsh conditions of which were said to have been the inspiration for the abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Her parents were Creole farmhands, and her grandparents slaves.

American Folk Art Museum, New York

When she was 15, having spent fewer than ten days in school, she moved to the nearby Melrose Plantation, working her way up from cotton-picking to the position of housekeeper and cook. By contrast to the dire Hidden Hill, Melrose was relatively liberal. The estate’s owner was a wealthy and educated woman named Cammie Henry who turned the house into a retreat for White artists.

American Folk Art Museum, New York

In 1939 an artist left behind a set of paints and brushes, which Hunter uncovered while cleaning. Using an old window shutter as her canvas, she began to mark out the shapes of a river baptism scene.

Museum of Fine Arts Boston

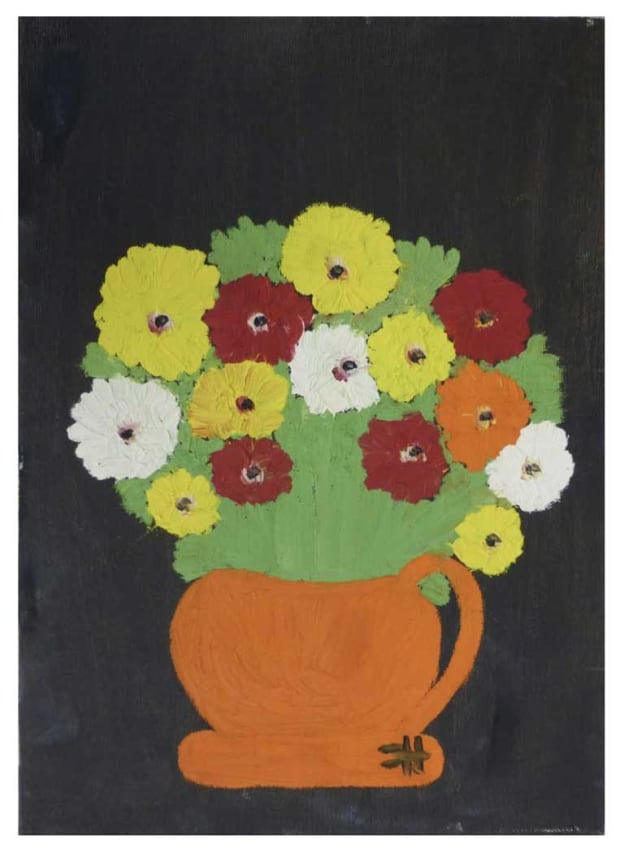

Hunter was soon working with everything she could find — bottles, gourds, cardboard boxes, and the tube-ends of pigment thinned with turpentine — and painted memories of farm work and religious ceremonies on the banks of the Cane River. Her childlike style was colorful, favoring surrealism over perspective. Asked why she painted a giant chicken pulling a cart, she quipped: “If the chicken wasn’t big, it wouldn’t be able to pull it.”

American Folk Art Museum, New York

Unable to spell her name, Hunter signed her works with a backwards C and H monogram and began selling them for less than a dollar. A sign on her studio door read: “Clementine Hunter, Artist. 50 cents a look.” To make a little extra, she also sold visitors homemade popsicles.

American Folk Art Museum, New York

Hunter may have started painting late in life, but she more than made up for lost time, creating more than 5,000 works during the second half of her life. She mostly worked at night beside a kerosene lamp in her four-roomed, tin-roofed tenant cabin, which is now listed on the register of Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios. Her masterpiece, a nine-panel domestic cycle on the walls of the Melrose Plantation’s African House, is a kind of Sistine Chapel of folk art.

You May Also Like:

Ernie Barnes’ Masterpiece, ‘The Sugar Shack,’ Realizes Record $15.3 Million

Mexican Artist Diego Rivera’s Work On The Rise