#Nevada #Museum #ArtSagebrush #Solitude #Maynard #Dixon #Nevada #Antiques #Arts #Weekly

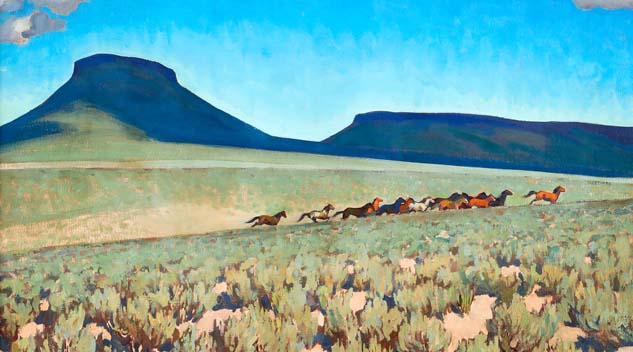

“Wild Horse Country [Humboldt County, NV]” by Maynard Dixon, 1927. Collection of the Society of California Pioneers.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

RENO, NEV. — In early March of 2024, a historic blizzard hit the Sierra Nevada mountains, stranding drivers in their cars with more than 80 inches of snow. Traffic was closed in both directions on the bridge crossing Donner Pass — causing news outlets to draw grim connections between the present-day extreme weather event and the brutal winter of 1846-47, when a group of some 60 pioneers from Illinois (the “Donner Party”) failed to cross the Sierras in time and spent the winter snowbound in the valley below, under unspeakable conditions that many of them did not survive.

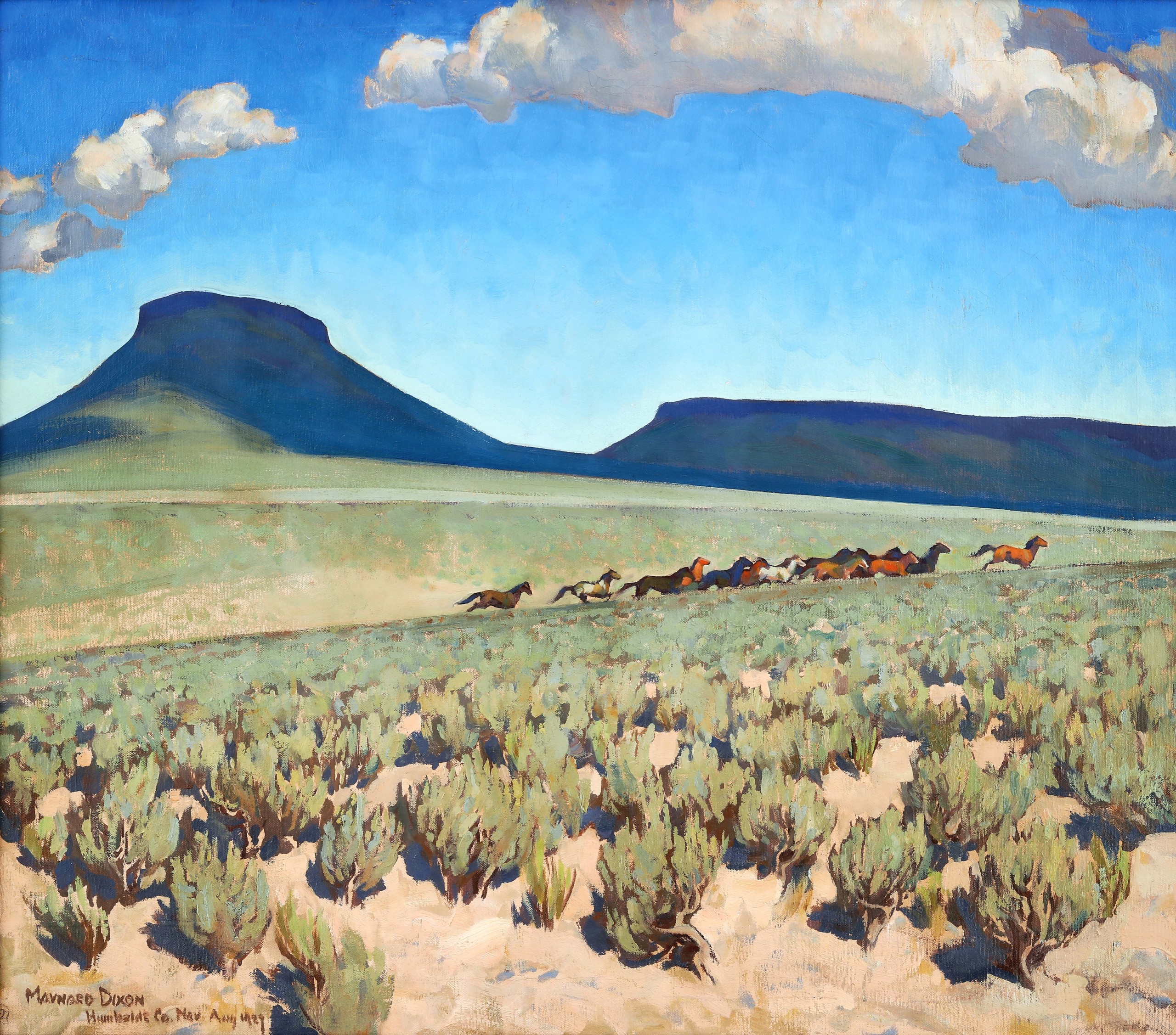

Less than 60 years later, Nevada’s Great Basin — the place that the Donner Party was so desperately trying to escape — would begin to be seen as an escape itself: an unspoiled wilderness just over the pass from rapidly industrializing San Francisco. This was its allure for the young Maynard Dixon (1875-1946), a commercial illustrator who first traversed the mountains on horseback in 1901 with his artist-friend and mentor, Edward Borein. Both artists were kitted out not only for wilderness survival but also for painting in the brush; one of Dixon’s sketches from that trip later ended up on the cover of Harper’s Monthly magazine. Exploring this period of artistic output is “Sagebrush and Solitude: Maynard Dixon in Nevada,” which is on view at the Nevada Museum of Art through July 28.

“Portrait of Maynard Dixon” by Isabel Porter Collins, circa 1895. California Historical Society Photographs from the Isabel Porter Collins Collection, MSP 422.

The title is a bit deceptive since, as Nevada Museum of Art curator Ann M. Wolfe explains, “People around the world, they think of the deserts of the American Southwest as these empty, unpopulated places, [and] they’re absolutely not that; they’re rich in culture, they’re rich in people, they’re rich in flora and fauna.” Beyond the settler-colonial fallacy of the West as largely unpeopled, it is also true that Dixon rarely visited the Great Basin in solitude per se; he was often with artist friends like Borein or, later, with his second wife, the photographer Dorothea Lange and their family. Nevertheless, it is clear that in these spaces he responded to something that was very different from the crowds of San Francisco or even from the agricultural bustle of the San Joaquin Valley, where he grew up. Apart from the cowboy and ranch scenes that were his bread-and-butter as an illustrator, his early paintings from Nevada meditate on the quiet meetings of plain and mountain: the way clouds and ridges and the area’s stark vegetation both capture and deflect the light, creating effects of color and atmosphere that seem unique and eternal.

Although Dixon first chose to venture to Nevada by horseback, rail service from California to the Great Basin — specifically Lake Tahoe, just south of Donner Pass — had already existed for decades. It was a relatively short trip from Sacramento and later, as Wolfe explains, from San Francisco, where Dixon was based and where he was a major figure in a circle of artists and writers who were constantly seeking new experiences. “We often say that northern Nevada is to San Francisco what the Southwest is to LA or Southern California…sort of an escape or a playground for people in the Bay Area.” This rising profile of the Great Basin as a place for recreation provided Dixon not only with more travel options but also with commissions for magazines and the tourist trade. Among those commissions was a mural cycle for the passenger steamship Silver State, featuring scenes from Nevada’s mining and cattle industries.

“Prospector with Mules” by Maynard Dixon, 1921, oil on canvas board, 14½ by 32 inches. Collection of Carolyn L. Fey.

But Dixon found something more meaningful in the Great Basin than just fodder for his commercial clients. “Everything there is vital and positive,” he told a reporter in 1919, “and there is no room for half-tones when you paint it.” He took regular trips to what he called “sagebrush land” to recharge, assuage his chronic asthma and find inspiration for his art. A 1921 trip with Lange and her extended family to the Inyo Mountains and Death Valley established visual memories that Dixon would continue to revisit for years afterward. Beyond the austere mountains and shifting shadows, Dixon was also drawn to the unique flora and fauna of the place: tufts of sagebrush fighting upward out of the arid earth, stands of cottonwoods or Lombardy poplars signaling a distant source of water, herds of wild horses coursing across the plains.

Dixon was deeply conflicted about the settlement of the West, reserving particular enmity for the encroachment of the automobile. Although he willingly rode in cars, thus taking advantage of the access they provided to the remote spots he loved to paint, he never drove one. In his poetry — he was a prolific poet as well as an artist — Dixon laments the time “before the automobiles and then prohibition came” and decries the “fools” and “dupes of ‘Progress’”: “Why would you do sadistic violence to Beauty? / How will you dare?” Yet he is much more candid about these concerns in his words than in his art. Those stands of trees he painted often mark the settlements that his poetry wished away — poplars are not even native to the area, nor are wild horses — and he did not shy away from rather heroic images of the cowboys and ranchers who were among the first to “settle” the West. Indeed, he even styled himself as a kind of cowboy, sporting a Stetson hat, boots and cape with his own proprietary thunderbird design, even while walking the streets of San Francisco.

“Pouring Cement [Boulder Dam]” by Maynard Dixon, 1934, oil on canvas, 30 by 25 inches. Private Collection. Photograph by Daniel Ballesteros.

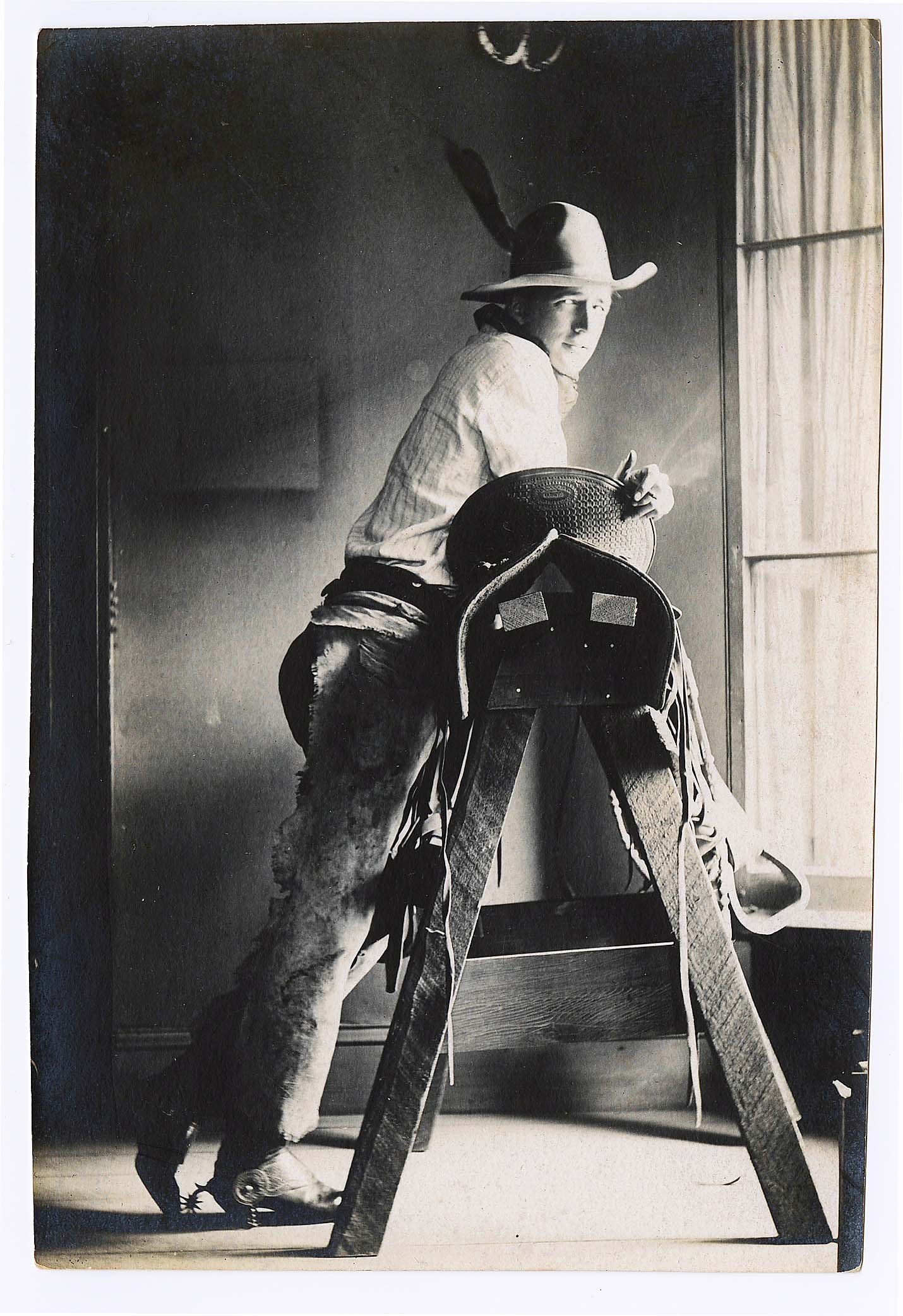

These contradictions are nowhere more evident than in his views of heavy industry in the Great Basin. In 1934, he was hired by the Public Works of Art Project to shadow the crew working on Boulder Dam (now Hoover Dam) and document their work in art. The dam was a defining project of the New Deal, a major improvement in infrastructure that employed thousands during a time when jobs were desperately needed — and yet the changes it brought to Nevada’s landscape were dramatic and irreversible. Dixon’s renderings of the dam under construction and the laborers working on it are not outright critical, as his writings about it sometimes are, but neither are they demonstratively laudatory in the way some other WPA-era art is.

“When it comes to the Boulder Dam commissions, he pretty much takes a middle of the road approach,” says Wolfe. “There was great pride, on one hand, in the broader society about the construction of this dam and what that meant — and [yet] what he witnessed at the dam in his writings is horrific. He knows that people are dying, he knows that people are in the hospital daily, but yet he seems to somehow not quite relinquish the pride of those men.”

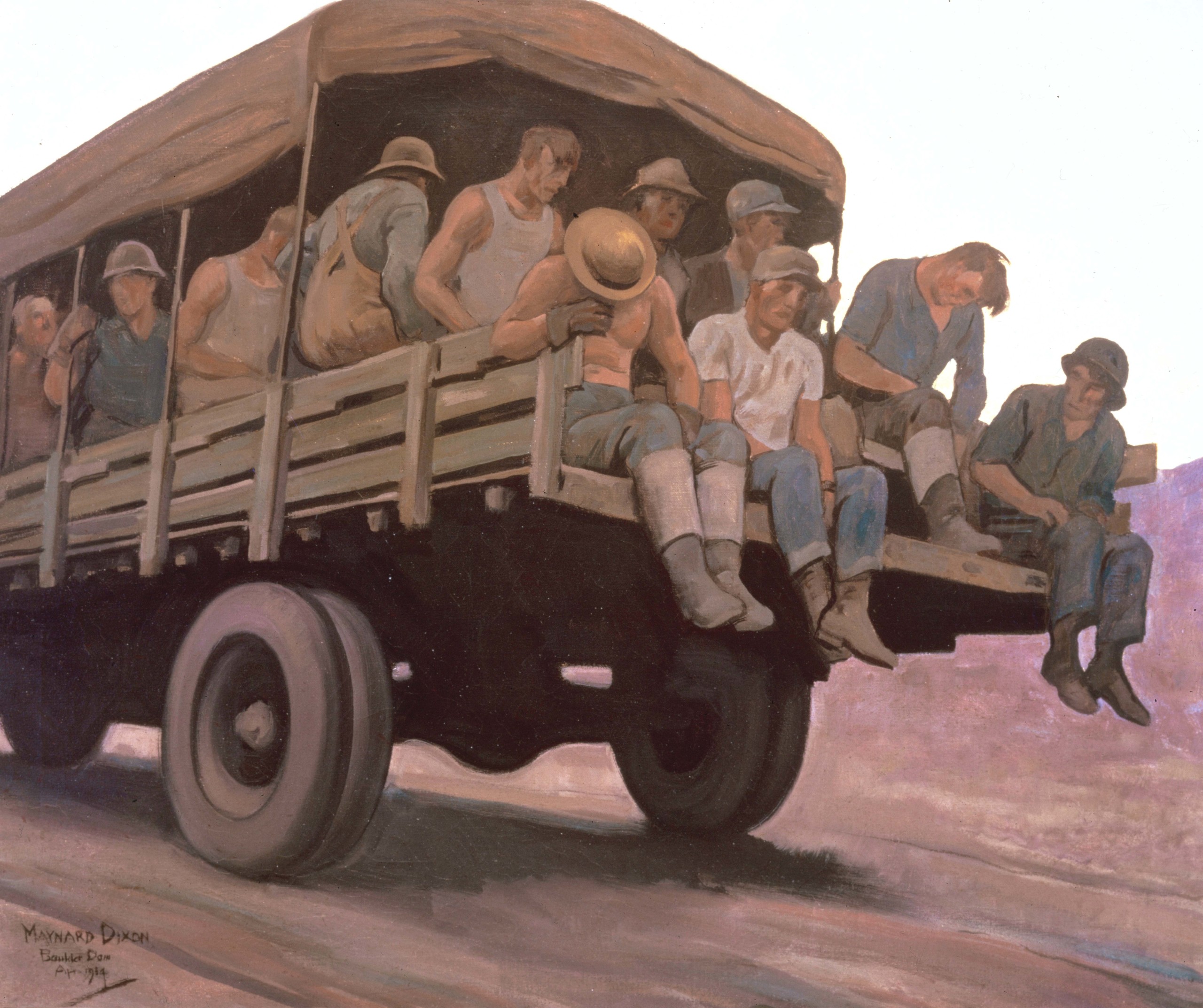

One case in point is the canvas “Tired Men,” showing laborers riding back to camp at the end of their shift, their legs dangling out the back of a truck bed, shoulders hunched with fatigue. The painting is both anti-heroic and heroic at the same time, a poignant testimony that labor is not some abstraction to be exploited or exalted but a lived reality. Art historian John Ott, in his thoughtful catalog essay about the Boulder Dam series, reads the men as “dissipated protagonists” and “defeated casualties of their war against nature” — though Dixon scholar Donald Hagerty writes that when Dixon exhibited the paintings in Boulder City upon completing the commission, “construction workers who viewed the exhibit judged ‘Tired Men’ their favorite painting.”

“Tired Men” by Maynard Dixon, 1934, oil on canvas, 25 by 30 inches. Private Collection.

The ability of Dixon’s paintings to shift both toward and away from multiple truths is something to which contemporary viewers should be attuned, says Wolfe. As she writes in the catalog, “although [Dixon] sought ‘ideals of truthfulness’ in his work, nowhere to be seen in his paintings are the often-violent frontier collisions of Indigenous people with American settlers, acts of vigilante justice, discrimination against immigrant communities, extractive mining enterprises or unchecked development in the name of progress.” One way of addressing that absence has been the catalog itself, where Ott deals forthrightly with racist and exploitative labor practices at the Boulder Dam project and literary scholar Anne Keniston mines Dixon’s poetry for passions and opinions that go largely unexpressed in his paintings.

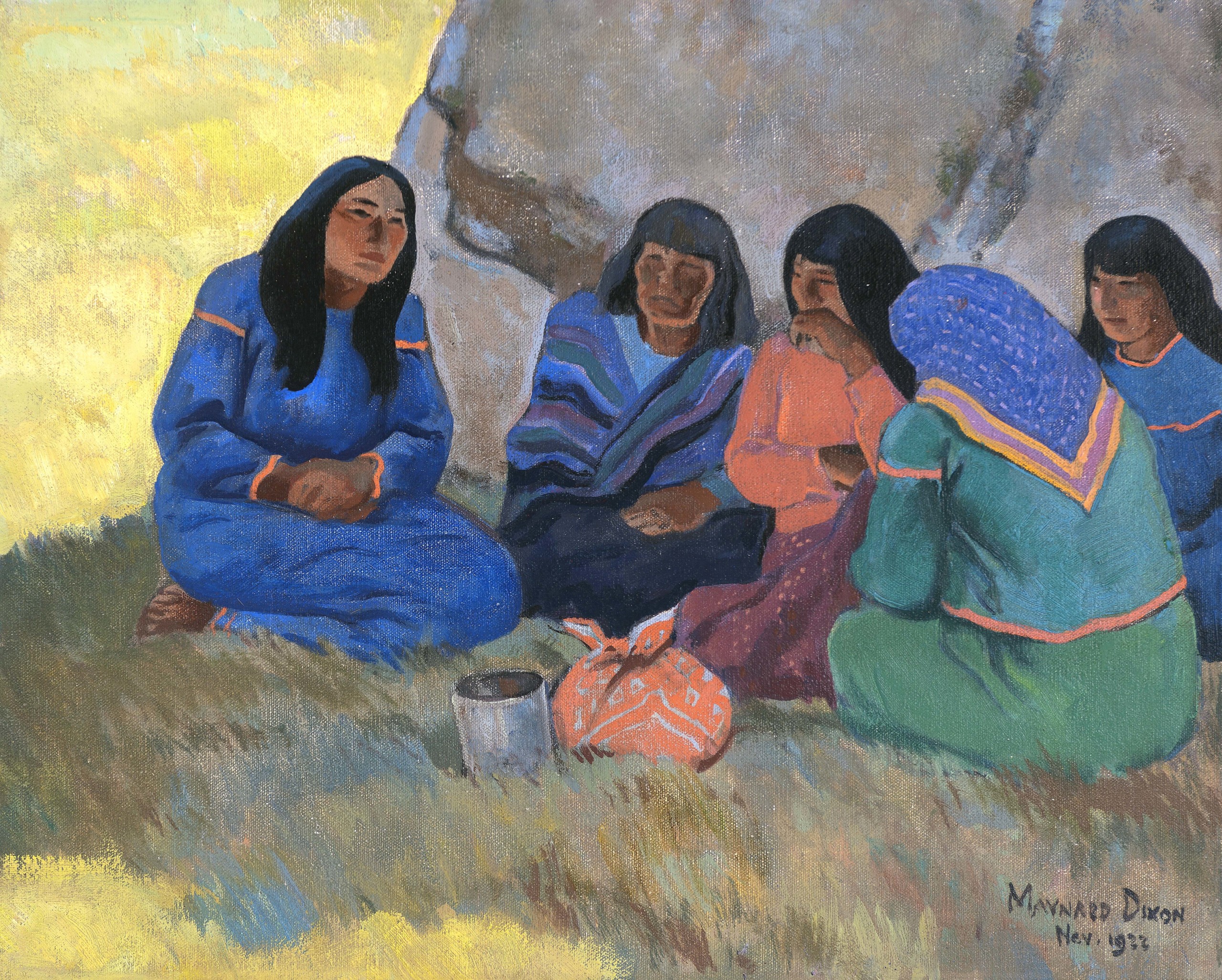

Another way of making space for multiple truths is through the use of community-written labels, a strategy that many other museums who display “Western art” have used recently to highlight diverse voices beyond those of the curators and the artists. Wolfe offers as an example two striking paintings by Dixon of Nevada’s wild horses, both exemplars of the modernist style that Dixon was among the first to practice in the state. A standard curatorial text might talk about just that — the partitioned color, the bold angles, the unusual vantage point — but community input ensures that the exhibition texts also address the complicated history of wild horses in Nevada and the ongoing debate about how and whether to manage their role in the area’s ecosystem. Here, too, is an opportunity to discuss the few portraits in the exhibition — rather sensitively worked and individualized portrayals whose titles nevertheless seem to present Mexican and Indigenous people as “types” — and works like “Washoe Soirée” of 1933.

“Washoe Soirée” by Maynard Dixon, 1933, oil on canvas board, 16 by 20 inches. Fulstone Family Collection.

The presence of these paintings in the exhibition — and in Dixon’s oeuvre writ large — once again complicates the idea of “solitude” put forth in the exhibition title. It is true that the Great Basin was an escape for Dixon from the crowds and society of San Francisco, and it is also true that most of his Nevada paintings are still and unpeopled landscapes. But it is also important to remember that these were not unpeopled places, and that he didn’t experience them in solitude, for the most part. Nevada was a place Dixon went to find himself — just as Wolfe observes, people still do today — but it was also a place he went with Lange to try to save their marriage (there is a section of the exhibition called “Love and Loss in Carson City”), to be with friends and extended family, to meet new people and experience different communities. In the end, the idea of solitude may be most relevant in that Dixon perhaps felt himself alone in decrying the inexorable transition of this wild land — once an existential threat to Nineteenth Century travelers — to an off-roader’s paradise.

The Nevada Museum of Art is at 160 West Liberty Street. For information, 775-329-3333 or www.nevadaart.org.