#Tapestry #Time #English #Antique #Furniture #Ages

The history of furniture in England is a captivating narrative of artistry, innovation, and societal transformation. From the humble origins of medieval simplicity to the opulent designs of the 19th century, English antique furniture has mirrored the evolving tastes, aspirations, and socio-cultural dynamics of its time. This journey through the ages unveils the distinctive traits and characteristics of key furniture pieces. Additionally, furniture styles shed light on the symbiotic relationship between societal changes and furniture styles.

Medieval Times: Form Follows Function

The medieval era in England, spanning from the 5th to the late 15th century, was marked by functional simplicity in furniture design. In an agrarian society, furniture was primarily utilitarian, reflecting a focus on practicality rather than aesthetics. Tables were rudimentary, often of trestle style with collapsible legs for easy storage. Chairs were a luxury, reserved for the nobility, and displayed a heavy, rigid structure. Oak, chestnut, and elm were commonly used woods, emphasizing durability over ornamentation.

The Renaissance Influence: 16th Century

The dawn of the 16th century witnessed the arrival of the Renaissance, an era of revival in art, science, and culture. English furniture, influenced by Italian and French styles, underwent a transformation characterized by ornate detailing and intricate carvings. Tables became more stable and elaborate, adorned with bulbous legs and stretchers. Chairs evolved with turned legs, upholstered seats, and higher backs, signaling a departure from medieval austerity. The use of walnut and oak added richness to the overall aesthetic, reflecting a growing appreciation for craftsmanship.

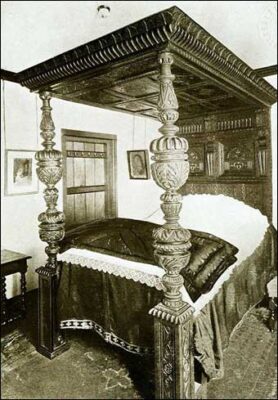

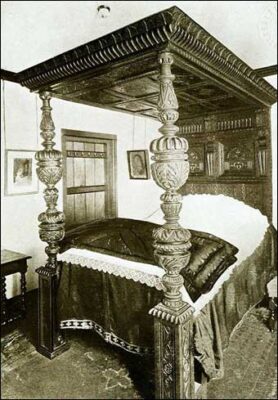

Jacobean Era: Early 17th Century

The early 17th century, known as the Jacobean era, continued the Renaissance influence but with a distinct English touch. Furniture of this period featured heavy, geometric designs marked by bulbous turnings, strapwork, and carved motifs. Oak remained the dominant wood, reflecting the continuity of medieval traditions. Cabinets gained prominence, showcasing intricate marquetry, and chests became multifunctional pieces, symbolic of the rising affluence of the merchant class. Beds, such as this one, had elaborate carvings and pillars of dark wood.

Carolean and William and Mary Period: Late 17th Century

The late 17th century brought forth the Carolean and William and Mary periods, each leaving its imprint on English furniture design. Carolean furniture retained the weightiness of Jacobean pieces but incorporated more exuberant detailing. Contrastingly, William and Mary furniture embraced a lighter and more graceful aesthetic. Cabriole legs, marquetry, and lacquer work became prevalent, ushering in a sense of refinement. Furniture during this period marked a shift towards more comfortable and relaxed seating, reflecting changing societal attitudes.

Carolean style work specialized in the use of walnut wood. Chairs of the time had light frames and tall raked backs. Backs and seats of the chairs often had caning although at first this consisted of simply a coarse mesh. Carving decoration was elaborate, employing carving of oak leaves, eagles’ heads, flowers, husks, and rosettes.

This William and Mary armchair demonstrates the increased degree of comfort, and showcases cabriole legs.

Queen Anne and Georgian Period: Early 18th Century

The early 18th century witnessed the Queen Anne and Georgian periods. They were characterized by a departure from the elaborate designs of the previous century. Further, furniture became more refined, featuring cabriole legs, scalloped shells, and restrained ornamentation. Mahogany emerged as the wood of choice, replacing oak and walnut. Queen Anne chairs, with their graceful curves and restrained elegance, set the tone for the Georgian era’s emphasis on symmetry and proportion. Societally, the rise of the merchant class and the pursuit of refined living influenced furniture designs, as prosperity and comfort became more attainable for a broader spectrum of society.

This high chest, with its powerful stance and ambitious ornamentation and elegant curves are an excellent example of the gorgeous style.

Chippendale, Hepplewhite, and Sheraton: Mid to Late 18th Century

The mid to late 18th century saw the emergence of influential furniture designers such as Thomas Chippendale, George Hepplewhite, and Thomas Sheraton, each contributing to the evolution of styles. Chippendale’s designs were characterized by elaborate carvings and a blend of Rococo and Gothic influences. Hepplewhite favored delicate, tapered legs and neoclassical motifs, while Sheraton embraced straight lines, inlay work, and geometric forms.

This period witnessed a shift towards a more refined and diverse range of furniture pieces. Bookcases, china cabinets, and writing desks gained popularity, reflecting a growing emphasis on education, intellectual pursuits, and personal correspondence. The availability of design pattern books also allowed for greater dissemination of styles, contributing to the democratization of furniture aesthetics.

Chippendale designed this chair along with fourteen others to make up this set of Neoclassical mahogany dining chairs for Daniel Lascelles, a patron of his. The chairs represent one of Chippendale’s most elegant designs: their tapering backs. Further the backs have arched top rails and molded sides headed by beaded paterae and leaf finials; fan-shaped splats with a central patera are encircled and flanked by pendent bellflower swags; and the square, tapering paneled legs are decorated with pendent husks.

Regency Era: Early 19th Century

The Regency era marked a return to classical influences and a departure from the strict neoclassicism of the Georgian period. Furniture designs during this time featured Greek and Roman motifs, with an emphasis on clean lines and symmetry. The use of rosewood and ebony added a touch of opulence to furniture pieces, catering to the refined tastes of the upper classes.

Societally, the Regency era was marked by a focus on elegance, sophistication, and a celebration of the arts. The influence of prominent figures like the Prince Regent (later King George IV) and the architect John Nash shaped the cultural landscape, influencing not only architecture but also the design and decoration of interiors. Furniture, as an integral part of interior design, reflected this cultural milieu, showcasing a harmonious blend of classical elements and contemporary refinement.

Crafted with a beautiful mahogany veneer, this set of Regency tables comes with its original additional leaf. The leaf which can be attached to the two Demi lune tables to create a spacious dining room table for up to six guests.

This decorative box is available on Styylish today, and dates back to 1830. The box features a lovely Rosewood and Palisander veneer. Its exterior exhibits a wonderful french polish, and brass trims cover the upper edge of the box.

Victorian Era: Mid to Late 19th Century

The Victorian era, spanning much of the 19th century, was a period of remarkable diversity and innovation in furniture design. The Industrial Revolution brought about significant changes in manufacturing processes, allowing for mass production and a broader range of materials. This era saw a fusion of styles, including Gothic Revival, Rococo Revival, and the Arts and Crafts movement Thus, demonstrating the eclectic tastes of the time.

This exceptional Victorian game table with backgammon, cribbage and chess board, originates from the 1860s. This rectangular table stands on a barley twist base, showcasing exquisite craftsmanship. The top is adorned with a kingwood veneer, adding a touch of elegance to its design. What sets this game table apart is its unique interior. With a simple flip, the table opens up to reveal a stunning inlaid wood decoration featuring a backgammon board, as well as a chess or checker board. This remarkable combination of gaming options makes it a truly rare and remarkable piece.

Mass production allowed for a wider distribution of furniture across various social classes. Therefore, pieces ranged from opulent and heavily ornamented to more practical and utilitarian. The development of new materials, such as cast iron and steel, also contributed to the creation of innovative designs, including the iconic bentwood chairs by Michael Thonet.

The Arts and Crafts movement, led by figures like William Morris, sought to revive craftsmanship and traditional techniques in response to the perceived soullessness of mass-produced goods. This movement had a significant impact on furniture design, promoting handcrafted pieces, simple forms, and natural materials. The game table on Styylish is the perfect manifestation of this notion, with its one of a kind, unique craftsmanship.

From Medieval to Victorian: English Furniture’s Legacy

The evolution of English furniture from medieval times to the 19th century is a testament to the dynamic interplay between artistic expression, technological advancements, and societal shifts. From the functional simplicity of medieval pieces to the opulent diversity of the Victorian era, each period reflects the spirit of its time. The changing socio-cultural landscape, influenced by economic prosperity, intellectual pursuits, and cultural movements, is intricately woven into the fabric of English furniture design, leaving behind a rich tapestry of styles and craftsmanship that continues to inspire and captivate us today.