#Victor #Weinblatt #Antiques #Arts #Weekly

When Antiques and The Arts Weekly received a press release headlined “Weinblatt Ceases Exhibiting at Shows,” interest was immediately piqued as to why South Hadley, Mass., dealer Victor Weinblatt, 77, a highly regarded specialist in American folk signage, would no longer be exhibiting at shows. Rhinebeck regulars would be dismayed, we believe, upon entering Building C over Memorial Day weekend not to see Weinblatt’s burgeoning display of folky signs and lively aphorisms that are his passion, so we reached out to him to see what was afoot.

You’ve been a regular at several major East Coast and New England shows for nearly 50 years. What’s prompting the decision to cease exhibiting at them?

In 2018, I had two major spinal stenosis surgeries that compromised my mobility and sense of balance. This winter my setup assistant, who handled the rigging, lighting, ladder and grunt work, retired. Try as we might, a replacement could not be found. We create a gallery rather than a booth at every show, using customized 9-foot walls and a complex interior wall design. We did perhaps the greatest booth of our career last August at the New Hampshire Collector’s Fair. All in all, reluctantly, it was time to give up shows.

Will you be maintaining your gallery in South Hadley? And if so, what days and hours of operation will you welcome visitors?

Our gallery of 1,800 square feet (the equivalent of seven of our show booths) has become the mainstay of our business. As a part of our rambling 1873 farmhouse, it is a visual delight with exponentially more display space than any booth I have ever done. It is by appointment and will welcome visitors all year round.

What will be the best online platform for folks to check out your current inventory?

Although I don’t maintain a website, my Instagram account will provide a sampling. A more thorough view can be furnished on request through extensive photos of the gallery tailored to a client’s interest.

What prompted your fascination with American folk art signage and how long have you been collecting?

In my twenties, I was an academic, studying and teaching literature and writing: the Word was the epicenter of my universe so I was therefore naturally drawn to the words and language of folk signage. Life came full circle: from Words on the Page to Words on the Board. I missed the visual stimulation of the decorative arts in my academic period. In the years at Harvard, early every Sunday morning I traveled to the flea markets in Amherst, N.H., and Norton, Mass. In 1979, I made my final escape from academia and founded my full-time antiques business, using my collection as inventory. My parents and grandfather were great collectors. About half of my father’s accounting practice consisted of antiques dealers. Growing up, on summer vacations to the Berkshires, Pennsylvania and Vermont, my family frequented their favorite antiques shops. I started collecting as a child.

You do collect and exhibit other folk art material than just signage. What are some of the other categories available in your inventory?

Painted furniture, figural and geometric hooked rugs and Nineteenth Century skarns as sculptural wall objects.

What are your collecting criteria?

In signage, as in other areas, original surface, form and color. The naïve and the whimsical. In signage, double-entendre, wit, puns, humor, the provocative, inept grammar, punctuation, colloquialism and malapropisms. Over the years, visitors have commented that my presentations leave them smiling and happy. One wag pointed out that it was a “visual anti-depressant,” but one that ended up costing him more than his medication.

Where do you find your material?

After 45 years of specialization, one develops a network of loyal dealers and pickers across the country. By reputation, signs start to find you. The most joyous and gratifying source is acquiring collections you have helped build. The one I am proudest of is that of John Wilmerding, grandson of the pioneer folk art collector Electra Havemeyer Webb of Shelburne Museum fame. John claims that the day he offered me his collection in Princeton was the first time in 25 years that he found me at a loss for words. The following summer he invited me to his summer house in Maine and to lunch at his sister’s. As we approached, covering her huge Nineteenth Century porch were some of the greatest signs I have ever seen, matched only by those within the splendid summer house. Half-way through lunch she asked me to sell her collection: only the second time in 25 years John witnessed me rendered speechless (anyone who knows me can appreciate how inconceivable that may seem). When I finally regained the power of speech, I said, ‘Yes and Thank You’ and inquired if there were any other sign-collecting siblings to prepare myself for.

Since you will be welcoming visitors who share your love for folk signage in your gallery, can you describe what they’ll experience?

The gallery adjoins our rambling 1873 farmhouse, Judd Farm, surrounded by perennial gardens and ancient, monumental trees. Imagine walking through seven of our show booths. It is an embarrassment of riches, ever-changing with fresh material; most visitors require a good part of a day to adequately experience it.

Are there one or two categories of signs that have sold the best over the years?

Food and sexual innuendo. A Nineteenth Century trade, a jackscrew, was one who lifted and moved houses. The Nineteenth Century trade sign read JACK SCREWS FOR HIRE. We hung it a minute before opening at Rhinebeck with a particular Jack in mind. Director of a Philadelphia art museum, he proudly displayed it for years in his office. Needless to say, it caused a near riot in my booth. About an hour’s drive from our home is Wantastiquet Mountain. At its base was an inn with a sign: WANTASTIQUET INN. Enough said. Freud was right.

Do you have a favorite sign that sort of epitomizes your outlook on life?

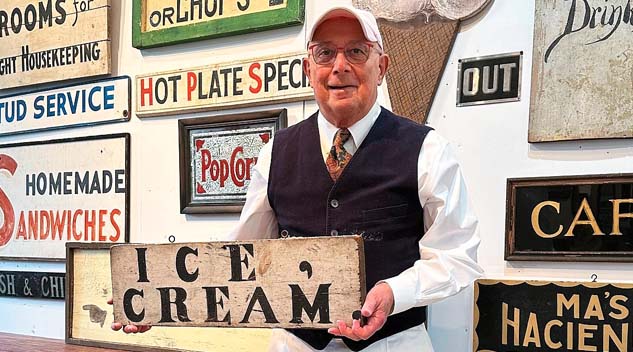

Five favorites. ICE CREAM, a circa 1890-1910 sign that I acquired from my late mentor, Fred Hansen. Each naive and graphic letter seems to derive from a different distinct font. The letters of ICE are extravagantly spaced, while CREAM has a more sensible prevailing spacing. A pointless and ungrammatical comma floats off in space, while a second hybrid comma/period completes the sign. The less people comprehend punctuation, the more they feel compelled to sprinkle it liberally like salt.

My late father, who helped me at shows in the 1980s and 1990s, attributed his great good health and longevity to a nightly bowl of chocolate Häagen-Dazs ice cream. So far, this philosophy has not exactly worked for me. Guess I need a larger bowl.

A second sign (one that got away) hung above Fred’s bed in Keedysville, Md., and read HE WHO LIVES SIMPLY LIVES SECURELY. It came up for auction in the sale of Fred’s collection shortly after his death in 1987. I chased it until it reached an astronomical price and I could imagine Fred saying: ‘The moral of this sign is not to pay this ridiculous price’ I lowered my paddle. I aspire to this philosophy, but quite unsuccessfully.

A third sign, LEISURE LODGE, a circa 1920 Adirondack sign with a diminutive manicule and exquisite surface and color. Philosophically, purely aspirational.

Antiques and folk signage are and will always be my life, full-time. Leisure has never been. Particularly since my surgeries, swimming is my daily therapy: a hundred laps a day, five days a week.

A fourth sign, HOT PLATE SPECIALS, a Maine diner sign from the 1930s. Superb color and graphics: the three red first letters absolutely stop you in your tracks and sing. I love to eat. My husband of 41 years, the unsung hero of my life, is a great cook, making those daily laps in the pool even more of a necessity.

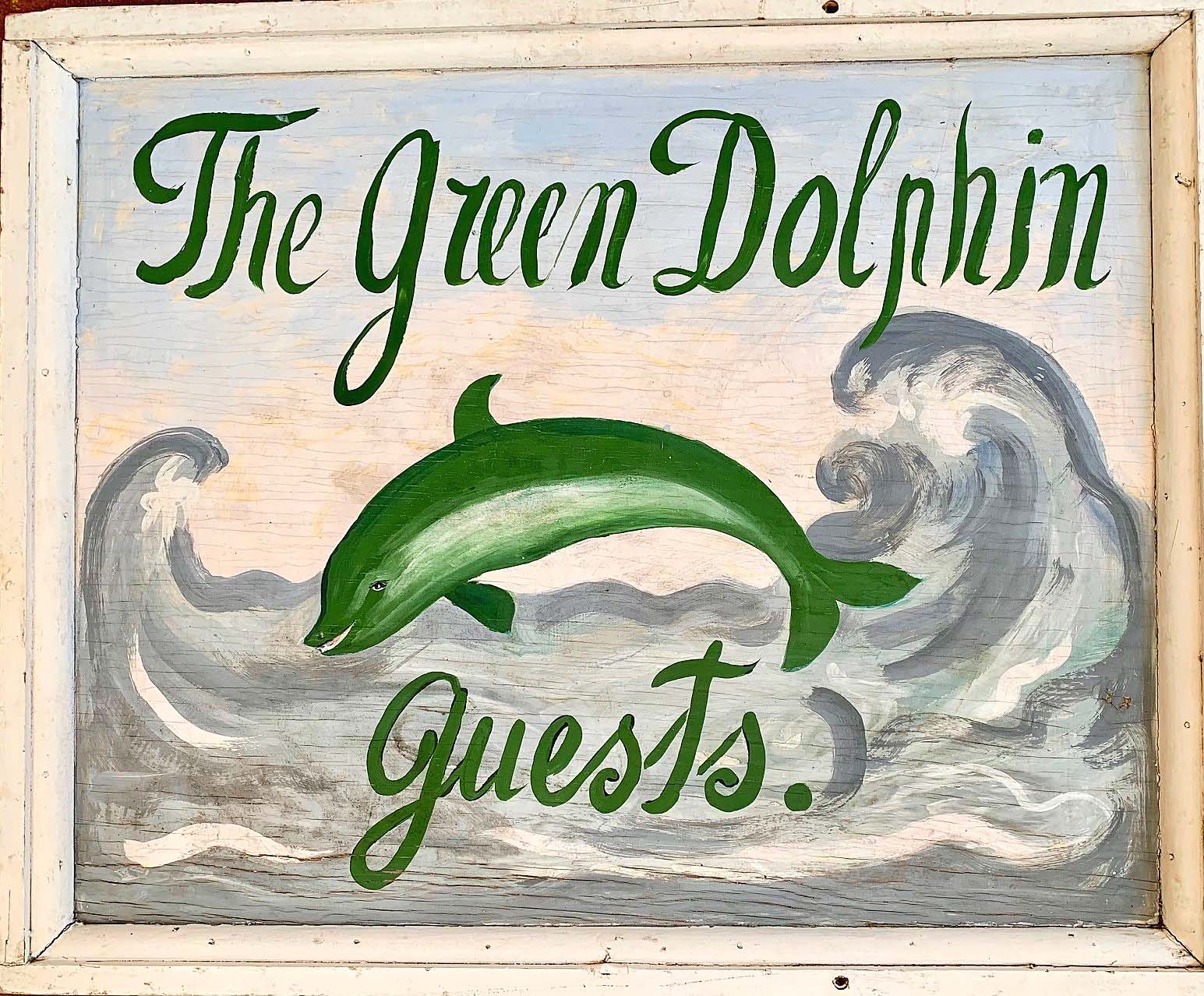

The fifth sign, THE GREEN DOLPHIN GUESTS, Old Orchard Beach, Maine, circa 1940. A laughing dolphin leaps from the waves in this kinetic figural tour de force. I have always loved the shore and swimming in the ocean; though not nearly as cute as a dolphin, I love to laugh.

I feel especially privileged to have experienced the Golden Age of the American antiques show.

—W.A. Demers