#Stephen #Fletcher #Antiques #Arts #Weekly

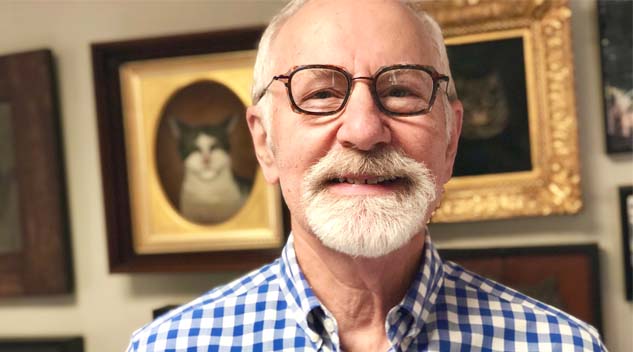

Through more than 50 years at Skinner’s and then Bonhams Skinner, recently retired executive vice president Stephen “Steve” Fletcher has been a major, trustworthy force in the world of buying and selling American furniture and decorative arts and more. He has assisted many prominent collectors in building their collections, and often, later dispersing those collections. He has stood at the podium, selling thousands of items, some for more than $1 million. He was an appraiser on Antiques Roadshow for 27 years. Along the way he, with chief executive officer Karen Keane, built one of the largest and most successful auction houses in New England. We had lunch with him recently, appropriately at Longfellow’s Wayside Inn, built in 1716 and once owned by Henry Ford, to discuss his career.

What got you interested in antiques?

No one in my family had any particular interest in antiques but I suppose, like many kids, I got interested in coins. When I got a pile of coins, I’d go through them, take out the ones that the coin books indicated might have some value and then take the rest down to the local supermarket where I could trade that pile for more and repeat the process. I’d go to the old Amherst, N.H., flea market every week and my first purchase was a painted tin dome-top box. I paid $8 for it, sold it for $12 and made $4. That’s all it took: I was hooked. Then I discovered old clocks and began to buy, repair and sell them. I did my first antique show when I was in the ninth grade. One day, I was able to purchase an eight-day Chauncy Jerome clock with wooden works and, to me, that was a treasure. I still love clocks, have a small collection, and add to it when I can.

When did you start working for Bob Skinner?

In 1962, Bob Skinner was just getting started conducting auctions in rented places like the Harvard, Mass., town hall. One day, after one of his auctions, he was helping me load some clocks I had just bought into my car. I was a teenager, still in school, but he offered me a part-time job, which I jumped at. I was his first employee, and we’d go around the shops in the area regularly and he’d buy stuff. That’s when I began to learn about furniture; he was a great teacher. We’d also go to auctions, which were real old-time auctions in those days. It was great fun for a kid: I met dozens of the legendary old-timers in the business and learned about buying and selling antiques. After graduating high school, I spent four years in the navy, and, when I got out of the navy, I went back to work full time for him. I had kept in touch throughout the four years I was away, especially with Bob’s wife, Nancy. It was a great time to be in the auction business: there was plenty of stuff coming out of the early New England homes and the company was busy and growing. Bob Skinner had been an engineer at Raytheon and understood the potential uses of technology. We were one the first auction houses, maybe the first, to computerize some of our operations. And as the company grew, we understood the need for specialist departments run by knowledgeable department heads. I think the first of those was for Oriental rugs. We went on to add several more departments. We all learned from one another. Karen Keane started with the company part time in 1978, going full time two years later.

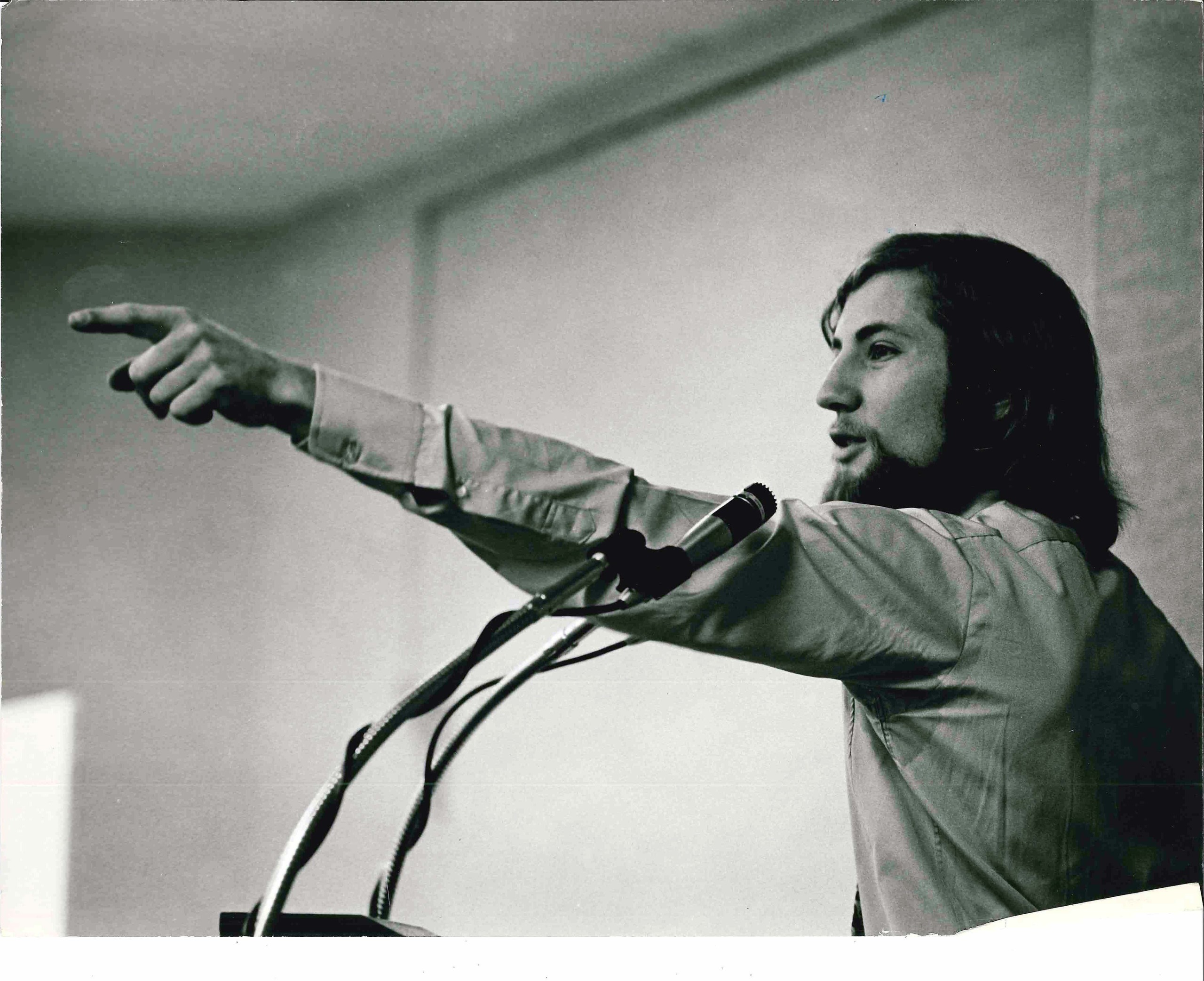

A young Steve Fletcher at the podium in the early 1970s.

How did you learn the fine points of American furniture?

That’s a simple question — on the job and from Bob Skinner. And many of the folks we did business with taught me a lot.

The company was headquartered in Bolton at the time?

Yes. Bob bought the gallery building in Bolton about 1971 and I think the first auction we had in that building was in 1972. (He died unexpectedly in 1984.) By 2008 we had outgrown that building. We’d run hundreds of sales there and by then it was obvious to Karen and I that we needed more space. Bob had donated some of the land in Bolton to the town for conservation purposes, so we could not expand that building and we started looking at larger buildings within the general area. We found the perfect place in the Marlborough building we’ve been in since then.

When did you and Karen Keane become owners of the company?

As I said, Bob died in 1984, and Nancy Skinner, his wife, sold both Karen and I one-third interests in the company in 1989. We were a three-way partnership with Nancy as president. In 2012 Nancy decided she wanted to sell her third of the company and she offered it to us. She said that Bob had often said that he hoped that one day Karen and I would own the company. So we bought her share, excluding the real estate, and at that time, Karen and I each owned one half of the company until we sold it to Bonhams in 2022. When Nancy sold her third to us, she kept her one third share of the Marlborough building. Bonhams did not buy the real estate so now they rent the building from the three of us.

Queen Anne Japanned maple and pine high chest of drawers, signed “Rob Davis” in script, Boston, 1735-39, sold for $1,876,000 on November 7, 2004.

Tell us about some of the outstanding things you’ve sold.

Well, we all hope to one day be at the podium and sell something for more than $1 million. It happened to me a couple of times and I came close a few other times. One of my personal favorites was a Queen Anne Japanned high chest with raised chinoiserie decoration that I hammered down for $1,876,000, with buyer’s premium. That was the highest price ever achieved for a piece of furniture in New England. I discovered it on a seemingly routine house call with my colleague, American furniture appraiser Martha Hamilton. The piece dates back to 1735-39, and was found in an old farmhouse in Lowell, Mass. It had never been out of the family of its original owners, and, best of all, was clearly signed on a drawer by one of the well-known Boston japanners, Robert Davis. It was in an unused room that we asked if it was okay to look in; you can imagine our reaction. (Another prominent New England auctioneer had the house call before Skinner and decided to pass on it.) The high chest was sold to Ned Johnson, founder of Fidelity Investments. He also bought another of the million dollar pieces, the King Hooper scroll-top bombe chest-on-chest for $1,766,000. I found that hidden in a barn while on a North Shore house call. In 2011, I was at the podium when Stephen Score, bidding in the room with his client on the phone, paid $1,270,000, for the beautiful Abigail Rose folk portrait by an anonymous painter. I’ll never forget that one. Score had asked me not to change bidding increments so that his client would not get confused. It opened at $75,000 and increased by $10,000 increments, so it took a while. But it was a record for a folk painting.

I also sold a few things that almost made a $1 million. One was a copper touring car weathervane with a driver. It had headlights, side lights and was in great condition. It was probably made by Boston’s W.A. Snow Iron Works, around 1910. Jerry Lauren, who was a serious collector of weathervanes, paid more than $940,000 with buyer’s premium for it. Another great folk portrait was “Boy of the Dorr Family” which sold for $866,000, and there was an Ammi Phillips double portrait of the Ten Broek twins which brought $880,000, both with buyer’s premium. That list could go on and on.

But I wasn’t at the podium for one of the most exciting things Skinner ever sold. In 2014, we had a huge Fencai Imperial Qing dynasty vase that we sold for $24.7 million dollars. That’s probably the highest auction price New England ever saw. Karen Keane said to me, “why don’t you sell it,” and I said she should, which she did. There were many more great things that passed through our hands.

Monumental Fencai flower and landscape vase, China, Imperial Qianlong period, sold for $24.7 million on September 17, 2014.

Was there a particularly humorous house call?

We were often dealing with some of the oldest families in the area, some going back to the Mayflower era. Many were quite wealthy and very “proper.” I remember being in a home on Beacon Hill and looking over a fine highboy. I was taking out drawers so I could see construction details. The elderly lady who owned everything saw me doing that and said, “young man, why are you looking at my underwear?” I eventually convinced her that wasn’t the reason I had taken her things out of the drawers, but that’s always stuck with me.

Who are some of the collectors and dealers you’ve worked with over the years?

I’m of an age where I was privileged to know some of the legendary dealers and collectors and be able to visit so many of these people in their homes. These are some of the best memories I’ve had. I’ve already mentioned Ned Johnson. He was a true gentleman with interests in many areas. During his lifetime, he was a major benefactor of the Peabody Essex Museum. I have fond memories of visiting Marguerite Riordon at her home in Stonington, Conn. Stephen Score was a favorite, and I remember him buying an early needlework pocketbook for which he had a lucite display case made. I had a great deal of respect for him. He was a very smart guy. There were a host of others: Barbara Streisand, Jane Katcher, Bill Lipman, Frank Levy, Hymie Grossman, Jonathan Trace, Willie Poster, various people from Colonial Williamsburg and Historic New England, Wayne Pratt, Leigh Keno, Gail and Don Piatt, Carolyn and Tom Brunk and so many more. These people had great taste and knowledge. I remember selling a group of things for Andy Williams; a consignment of just 23 things that brought more than $2 million. He had a great eye. Some folks were very picky about our catalog descriptions; Merle and Jay Weiss actually helped us write the catalog for their sale.

Have you ever talked a person out of buying something?

Well, two things come to mind for that question. We had a nice, cherry dining table with its original surface. The woman I was talking to asked me if it could be refinished; I simply said, “This isn’t the table for you.” And during the preview for the Roger Bacon sale, a woman said to me, “Why does everything look so old and worn?” I had to say, “This isn’t the auction for you.” There were others but these stand out.

For a final comment?

It was great career; I loved every minute of it. As a young teenager I had started my journey on the long and winding road which beckoned me to a lifetime of work which I loved until my retirement. I am a fortunate and grateful man. As the Gershwin song goes, “Who could ask for anything more?”

—Rick Russack, Contributing Editor