#Ryan #Matthew #Cohn #Antiques #Arts #Weekly

Regina M. Rossi and Ryan Matthew Cohn. Photo courtesy of David Zeck.

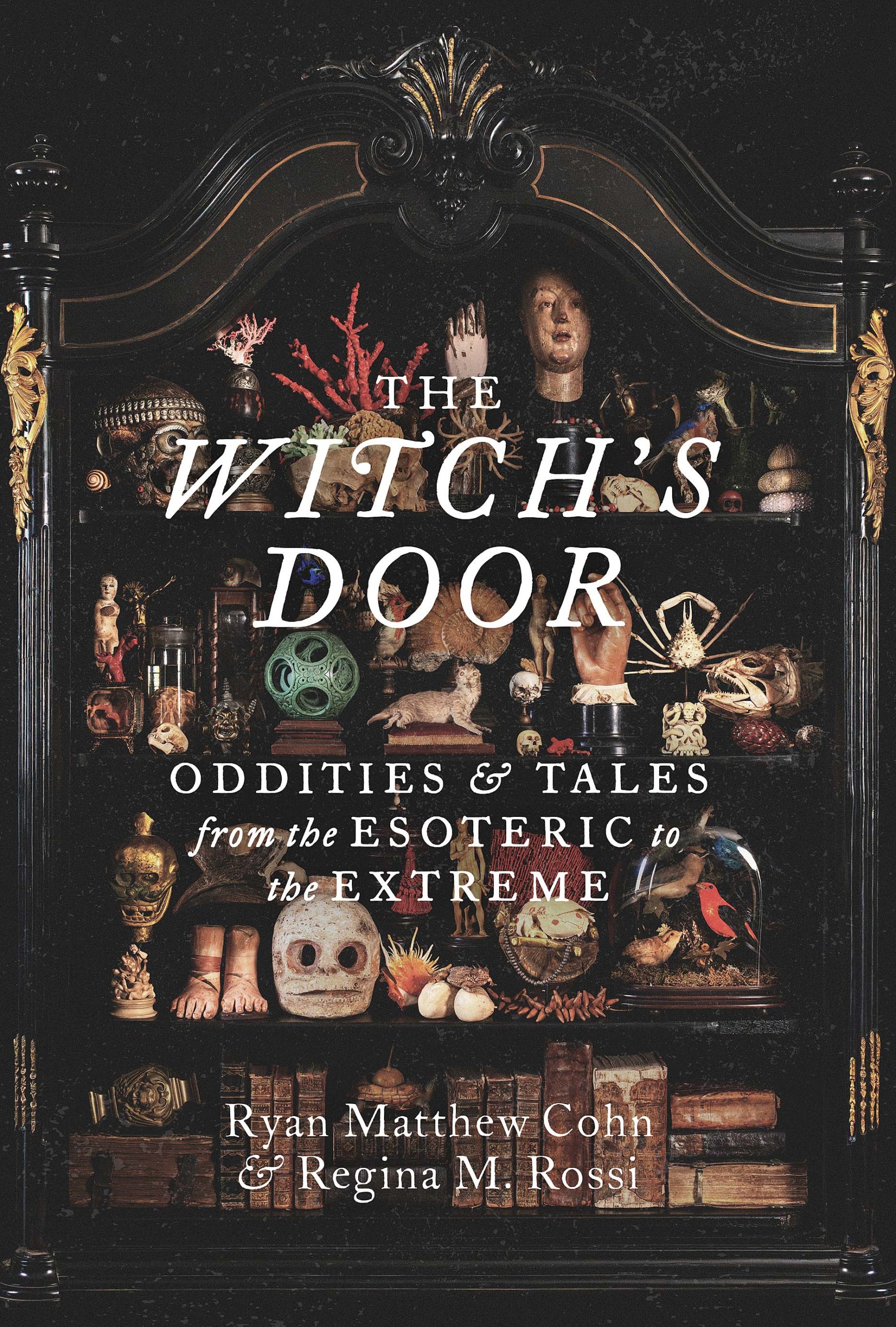

Ryan Matthew Cohn, with his wife Regina M. Rossi, is the co-founder of the Oddities Flea Market and, most recently, co-author of the book The Witch’s Door: Oddities & Tales from the Esoteric to the Extreme. In addition, Cohn is an artist, curator and art collector. To celebrate the release of their first book, we caught up with him to discuss The Witch’s Door and their lives as collectors.

Congratulations on the publication of your first book, The Witch’s Door! Could you tell us a little bit about the book?

The book is about my story and my wife Regina’s story, dealing with objects throughout our whole lives. We have been asked the question, ‘What do you do for a living?’ pretty consistently throughout our careers and it was one of those questions that was very difficult to answer because we do a lot of different things.

At the base of it all, we collect — or I collect, more specifically. And the stories… when we would tell people, they found them very interesting. You get sort of desensitized in this business if you do it enough or for a long enough period of time, something may sound fascinating but it’s just part of what I do. But when we tell the stories, people are really captivated by them, and they want to hear more.

Collections always change, so we thought it’d be really interesting to write a book that was about the stories involved in procuring rare antiques, either piece-by-piece or as an entire collection, and put them all into more of a storytelling memoir of sorts. The book is really different stories or our favorite stories that we chose to include. There’s always a story and the story, in some cases, is much more interesting than the actual object.

Can you share a favorite story or anecdote from the book?

They all stand out! The Nick Parmesan story is so interesting because it is one of the largest collections we have procured in the last five years. It was such a broad spectrum of antiques, and it took a couple of years to fully go through it and to go through the paperwork. Actually, the catalyst for the book in a way was that collection because that’s where we found the witch’s door. Nick was a friend of mine and when he passed away, the family basically said they’d sell me the collection, but I had to take everything. He had great stuff in his collection, but he also had a lot of random junk that he had picked up. Mixed into the collection was this unassuming, extremely old-looking door. It looks like a door that should just go down into a wine cellar or an old basement. It’s a pine door with cast iron or hand-wrought iron hardware but then if you look closely at the door, it has some crude carvings on it. We didn’t know what it was at first glance. We just told our people, ‘all right, load this up, put it with the other tall rectangular objects’ and we’ll figure it out later. I’d say it took about a year to figure out what that door was because we finally got to one of the boxes filled with paperwork. As it turns out, it was a Seventeenth Century door from New England that had come from this collector named Roger Bacon, who specialized in early rare folk art. It was potentially used to house someone accused of witchcraft. Once we learned that we realized we had to try to figure out all the rest — the where, when, why, how. And we’re still doing that. So, the book starts with that story, it’s mentioned again in the middle and then it kind of ends with the door, too.

The Seventeenth Century witch’s door. Photo courtesy of David Zeck.

So, this beginning, middle, end story of the door, that’s where the title The Witch’s Door originates?

Well, first of all, I liked the name because it has a good sound to it. But I liked that story because it’s ongoing and it shows that you don’t always come to conclusions right away. As a collector you can have a piece that takes decades to figure out. Then in some cases, you figure out that it wasn’t what you were told and it wasn’t very special, but you still have to go through that journey. You still have to do the research and oftentimes deal with experts on the subject of whatever subject matter you’re dealing with. We are taking the door to Salem and we’re hoping that there’s specialists there that can look at it and, you know, keep its story going.

How is the book organized?

It’s not in any real chronological order. We thought it would be interesting to tell the stories from both my perspective and Regina’s. The truth of the matter is that I have very different eyes when it comes to collecting than she does. She’s usually the voice of reason while I’m more like ‘let’s just do it!’ I have this mentality, just from being in the business for so long, if you don’t procure it in some way, someone else is there waiting. Regina is a lot more logical. She’s like, ‘okay, well, look, we only have so much space’ or she’ll bring up some of those practical points. So, we thought it would be really cool if we could both tell our stories.

“Portrait of a man / A Skull in a Niche” by Barthel Bruyn the Elder, circa 1535, double sided painting. Photo courtesy of David Zeck.

Who do you see as being the audience for The Witch’s Door?

I think it’s actually a broad spectrum of people that could enjoy the book because in one sense, yes, if you’re interested in oddities as what you collect, or you relate to it in some sort of way, or maybe you like the dark side a little bit, because some of this stuff could be construed as such. But I think it’s broader because I think it shows how some people live a little bit differently. And I think people in general inherently have this interest in the macabre or things that are out of the ordinary. I mean, just turn on your TV and go to Discovery Channel or History Channel — there’s all these shows about paranormal investigation or people buying and selling weird things or even my show Oddities was focusing on it specifically. But I think people have an interest in it and a lot of people don’t really know that there’s this subcategory of people that specifically collect this type of stuff. I think anyone could really gain interest in learning that some people make a living off of doing something that maybe they’ve not heard about. Or that there are black sheep out there that they could relate to. So, I think it wasn’t a book that we specifically wrote for ‘our people’ — we wanted to make it a little bit broader of a spectrum and I hope we have.

What would you most like readers to take away from The Witch’s Door?

I want people to see that there’s other ways that people live and other interests that people have, but we all have a common bond. I think sometimes when people get squeamish about death-related art or antiques I have to say, it’s the one thing that we technically all have in common. We’re all going to die at one point, right? So hopefully looking at these images opens up a conversation about death, or people could share stories about their experiences with death and maybe even loss. So, I think it’s this broader spectrum to evoke more of a conversation on it.

The Witch’s Door: Oddities & Tales from the Esoteric to the Extreme by Ryan Matthew Cohn and Regina M. Rossi. Chronicle Prism, San Francisco, 2024, pp. 282, $30, hardcover.

Some folks may consider the collection of oddities relating to death and human anatomy as disrespectful. How do you counter that presumption?

I think that when people are confronted with death, you either have the people that are accepting of death or the people that are very scared of it. So, instead of talking about it or living with it they ignore it, or they put religion in front of it. And it’s something that I’ve always been comfortable talking about and living with. And when I say living with, I mean living with art related to death or artifacts that are related to death in some way, because they’re just as important to me as any other painting in a museum. And if you go to any major art museum, most of the early works have to do with death in some way. It could be the death of a saint or the death of Jesus. A lot of the works deal with that subject matter — maybe some of them are a little bit more subtle than others, but some of them are very specific and they’re definitely revered as works that people like to enjoy and look at.

—Carly Timpson