#Joel #Antiques #Arts #Weekly

Ridgefield, Conn., resident Joel Third has been interviewed here before. It was in January 2020, just before the global outbreak of Covid-19 changed the way we live in the world for the foreseeable future. He sat down with then-editor Greg Smith to talk about his collecting career, a talk that was primarily focused on Third’s general art collection, which is prodigious. This time Antiques and The Arts Weekly wanted to learn more about the avid art collector’s remarkable collection of floral prints spanning five centuries.

What sparked your interest in art, particularly floral art?

We are always involved with flowers throughout our lives from beginning to end. Their beauty and colorful prints were always appealing. Because my profession as a communications engineer required the use of maps, they sparked my interest in print collecting, especially antique prints. From that exposure, it was an easy move to include floral prints in mine and my late wife’s collecting interest because of their colorful beauty.

Tell us about some of the floral print highlights in your collection.

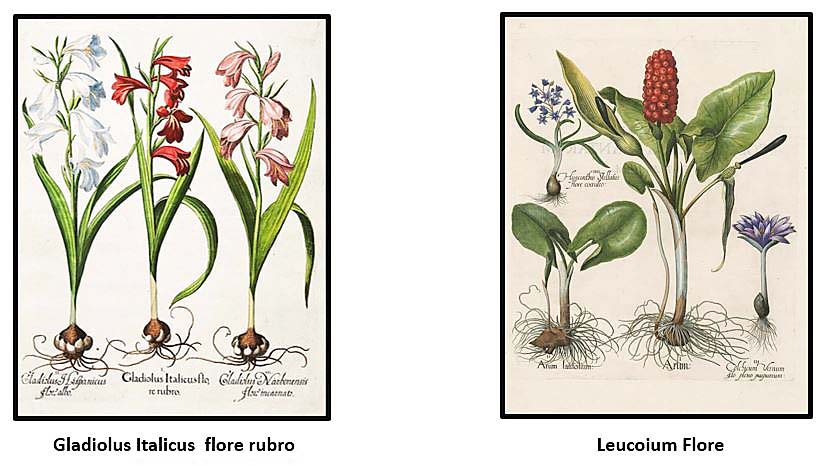

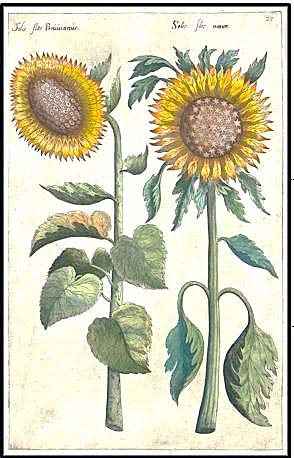

The prints that stand out in the collection are the ones from the Seventeenth Century. Basil Besler published a monumental floral document, a florilegium, called Hortus Eystettensis in 1613. The collection contains a few of the original, large, hand-colored prints. Emanuel Sweert published a plant catalog in 1612 for the Frankfurt Fair to market his bulbs and flowers. The collection does have a few of these original prints. While not as dramatic as the Besler prints, the Sweert prints are attractive. As an important part of America’s colonial history, I enjoy the prints of Mark Catesby, an English naturalist-explorer, who, in the early Eighteenth Century, explored the English colonies of Carolina and Virginia recording the flora and fauna. He engraved, colored and published in 1731 and 1754. Prints from Catesby are an accurate depiction of the colonies’ plant life that existed.

From a beautiful presentation of color perspective, the Nineteenth Century prints of Pierre Joseph Redoute are hard to exceed. These prints copied from watercolors were published from 1830 to 1950.

Basil Besler (1561-1629) from Hortus Eystettensis, 1613.

Do you differentiate the art of botanists versus artists in general?

Not really; however, I do realize that in general the botanists made more precise renderings rather than did the artists, since much of their work was motivated by commercial or scientific reasons. The artists were and are capturing a beautiful image. They both created attractive prints. A good example of a botanist’s work is that of Catesby, who had to produce precise prints to satisfy his science-backers back in England; in doing so he made attractive prints sought after today.

Some months back you gave a talk at the Ridgefield Library looking at evolution of artistic technique and styles in floral prints through five centuries — Seventeenth through Twenty-First. How did you come to look at the collecting category in that way?

When looking through the collection, I realized the flower images did, in fact, evolve over the years. In general, they became more impressionistic and less realistic. This change has been explained and was due to the different motivations, science, marketing versus artistic images in creating the prints, at least in this collection. Another factor is the evolution of printing techniques from intaglio, which consisted of engraving, stipple engraving and etching — all methods of cutting the surface of a metal plate to accept the ink for printing. The printed image was then hand-colored. Then lithography was invented in Germany in the late Eighteenth Century by drawing images on a limestone with a greasy crayon, then wetting the stone, applying ink, which adhered only to the drawing and printing occurred. The principle utilized was that water and grease or oil don’t mix. It initially made only black and white prints, which had to be hand-colored. Later on in the Nineteenth Century, color lithography or chromolithography developed using multiple stones, which required precise alignment. The printing of exotic flowers excited the public with all the varieties from all parts of the world. The lithographic prints were not as precise as the engraved prints, but produced a less expensive print available to the general market. Floral prints in the Twenty and Twenty-First Centuries are more impressionistic. Other printing processes developed as well. So, the genre has expanded and absorbed many different styles, but the special charm of the centuries-old floral prints remains.

Pierre Joseph Redoute (1759-1840) from Bouquet des Fleurs / Fleurs de Redoute, 1830-1850.

What was the earliest great floral publication?

I consider the Seventeenth Century florilegium, Hortus Eystettensis, by Besler printed in 1613 to be the earliest greatest floral publication, certainly in Europe. This florilegium contains 367 floral prints of more than 1,000 varieties of flowering plants. The publication was the collaboration of two men, Besler, a Nuremberg apothecary, and his patron, Johann Konrad von Gemmingen, prince bishop of Eichstatt, Bavaria (1561-1612). The prince created a comprehensive garden in Eichstatt and employed Besler to manage it and produce a catalog documenting the garden’s many plants. It took Besler 17 years to complete the hugely successful Hortus Eystettensis. Besler employed six engravers to assist him engrave the large (21 by 16¼ inches) copper plates and hand coloring the 367 prints. There were many editions of this attractive monumental publication.

You have some Ridgefield residents — all living — listed among your example of artists in the Twenty-First Century. Can you tell us a bit about their floral art?

The following artists live in the Ridgefield, Conn., area and I acquired their paintings, watercolors or prints from local sales:

Ann Kromer, a former Ridgefield artist, now a Cincinnati one, paints from nature in a loose, impressionistic, colorful style. Her landscapes and gardenscapes have won numerous awards and has exhibited in shows throughout America, including New York City’s National Arts Clubs. The collection has many of Kromer’s small floral watercolors.

Tina Cobelle-Sturges is a well-known local artist best known for her radiant, colorful paintings with an impressionistic and folk-art style. Her work demonstrates her ability to strike a balance between realistic and impressionistic genres, especially in busy urban streetscapes of New York City. Sturges seamlessly weaves nature and floral elements with the urban landscapes, resulting in a simultaneously energetic and soothing composition.

Tina Phillips is a local artist who has stated, “It’s a beautiful thing when career and passion come together…” She teaches at Founders Hall, a Ridgefield Senior Center. She has managed art shows for herself and her students. She paints in a colorful impressionistic style in watercolor and oils. She painted the Keeler Tavern Museum’s walled garden showing spring flowers.

Tina Phillips, a Ridgefield artist, has stated, “It’s a beautiful thing when career and passion come together. At an earlier age I realized I had a gift of art, so then my purpose was to share my gift.” She teaches art at Ridgefield’s Founders Hall, which gives her a good opportunity to share her gift. She paints in an impressionistic and folk art style.

Spencer Eldridge renewed his passion for oil painting in 2002 after spending time in the woods of upstate New York. He paints en plein air in order to capture the ever-changing effects of light as it falls on nature. Eldridge’s work has been exhibited in galleries in Los Angeles, New York City, Westchester County, N.Y., and Connecticut and hangs in many public and private collections. He has been an art teacher in the Katonah, N.Y., Lewisboro School District.

Carmen Lund is a local area artist and is on the faculty of Silvermine School of Art in New Canaan, Conn. She paints her floral works in an impressionistic free style that I appreciated and included her painting of tulips in the collection.

What are some tips for the beginning collector with regard to ensuring bona fides of a prospective item offered at an antiques show or at auction?

This is a very important question, especially for those starting a collection. I have noted some tips that I have learned from many years of collecting, a very rewarding hobby.

1) Always seek established dealers for items, as well as for advice. Dealers such as The Old Print Shop in New York City and others with decades of serving the collecting public. As far as auction houses go: Swann Galleries in New York City or Trillium Rare Prints in Franklin, Tenn. They all are on line.

2) Good reference books are important. The Art of the Garden, Collecting Antique Botanical Prints by Denise DeLaurentis and Hollie Powers Holt, published by Schiffer Publishing Ltd., Atglen, Penn,, 2006, is a very informative and attractive reference book.

3) Always try to collect original printings. If not sure, be sure to ask.

4) Try to choose a subject or grouping and don’t have a scattered collection.

You’ve retired and now have time to exhibit and present related talks. When did you retire?

I retired in 2007 from 47 years as an electrical engineer working on communications projects all over the world with International Telephone and Telegraph.

Emanuel Sweert (1552-1612), “Solis Flos Peruuianus” (Sunflowers) from the Florilegium Amplissimum et Selectissimum, 1612.

I know it’s a hard choice, but do you have a favorite print?

Yes, I think I do. I like Emanuel Sweert’s “Sunflowers” from his 1612 publication. I like the simple antique presentation of lovely sunflowers.

How do you display and store the collection?

I archivally frame what I can and the rest are in a flat file.

—W.A. Demers