#Joel #Bohy #Antiques #Arts #Weekly

Joel Bohy at the Little Big Horn battlefield in 2016.

The term ‘history detective’ becomes more apt when Twentieth — and Twenty-First — Century scientific methods are introduced to help further understand long-past historic events. Joel Bohy, who is director of historic arms and militaria at Bruneau Auctions by day, spends his off hours helping apply forensic and ballistics research to historical conflict sites. He shared some of his recent work with Antiques and The Arts Weekly following a recent lecture he presented on the topic at the Sharon Historical Society.

Has forensic/ballistics research has been used at archaeological sites for a while?

This type of research began in the 1980s at the Little Big Horn battlefield when archaeologist Dr Douglas D. Scott began using it on the project he was doing. Doug expanded the methodology and tried new things over the years which in the end gave a new historical understanding of the battle. I remember watching documentaries on TV where Doug was interviewed about his work, and it fascinated me. Over the years I read every book that he published.

How and when did you first get involved?

I grew up in Concord, Mass., and became infatuated with the history of April 19, 1775, as a 7-year-old. I read everything I possibly could about the battles, walked the battlefield, and absolutely loved the material culture. I spent many years hitting local museums and historical societies tracking down and studying April 19 objects. In the late 1970s I began to volunteer at Minute Man National Historical Park, and, around 2011, the park began to talk about doing an archaeological project at a site called “Parker’s Revenge” on the Lincoln/Lexington line. I was on the advisory board for the project and when it was time to do the fieldwork, I was allowed with a few other volunteers to do the fieldwork, but we had to be trained, and our expert the park hired was none other than Dr Scott. Over the two-year project, Doug and I became friends and talked about live fire studies we could do as well as using new technology to better understand battles of the past. He also suggested that I take classes on proper methodology for metal detecting on conflict sites, which I did numerous times, becoming an instructor on the course. With a group of the instructors at the course, we came up with other studies we could do to better understand the ballistics of historic arms. Over a three-year period, we did two live fire studies and published the data.

What can live fire tests tell us that are not apparent otherwise?

The live fire data was very important to our future work. We had a professional ballistician who recorded all the musket data for us, like the muzzle velocity. We shot at different media and metal detected each shot. Under magnification we looked at the ball recording what we saw, and we came up with a deformation index that could give an idea of what the ball might have struck, as well as a range of velocity that the ball might have had. This is published in our first report and is currently in use by conflict archaeologists when writing their reports.

What is a blind study and why is this important in the research?

So, the blind study was important to us as it was a way for other archaeologists who study fired musket shot to look at all our fired ball and record the data they see. After we received the data from them, we compare it to what we found. It was very interesting to see how it all came together to validate what we had recorded.

One of the more notable projects you’ve reexamined through this lens of forensics research is one at the Jason Russell House in Arlington, Mass., the site of a battle on April 19, 1775, the first day of the American Revolution and home of the Arlington Historical Society. Has this new kind of research rewritten the history of that day?

I wouldn’t say it has rewritten the history of what happened at the Jason Russell House. We were able to systematically and scientifically go through the house and record each bullet strike, what caliber the ball was, where the shots came from using modern shooting incident reconstruction. What it did do was really add a human element to the story as well as to really see the ferocity of the fighting in the late afternoon of April 19. The fighting was brutal, and our research shows that. At least 12 Provincials were killed in and around the house, and we really don’t know how many British soldiers were killed in that area. During the study at the Jason Russell House, we decided we should record all the known bullet strikes in structures and objects from that important day and publish it. The book is close to completion, and it will be out for the 250th of the battle in 2025.

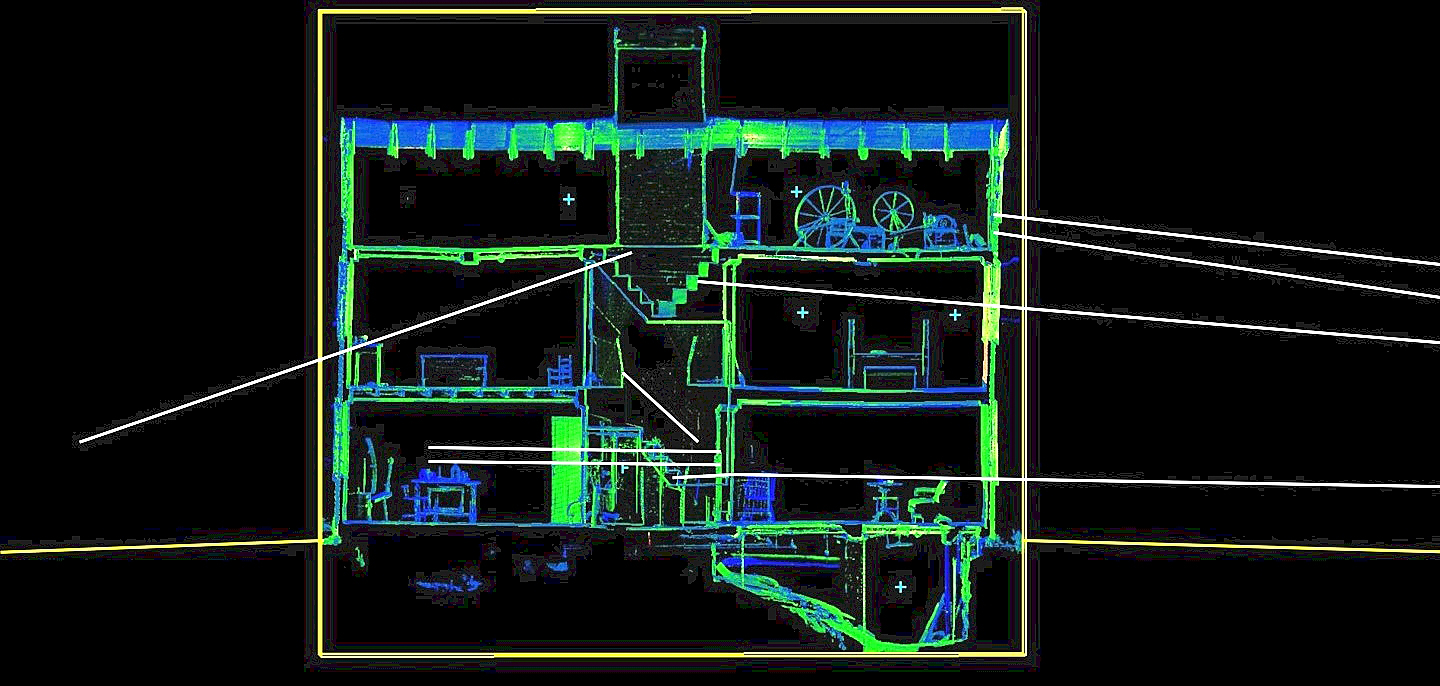

This 3D scan of the Jason Russell House allowed for a cross-section to be produced that helped Bohy and researchers project the likely shooter positions based on the trajectory analysis of the extant bullet holes.

Have you been involved with other similar projects?

I haven’t done other bullet strike work yet, but I have done many projects volunteering with professionals on the archaeology end. I’ve worked at Gettysburg and many other battlefields of the Revolution, as well as a few sites from the French and Indian War.

You’re director of historic arms and militaria at Bruneau Auctions in Cranston, R.I. Does this kind of scientific inquiry have any bearing on how you consider antique weapons that come to market?

Because of archaeology work and the live-fire ballistics study, I do look at historic arms in a different manner. I have a much better understanding of how they function, what they can do. I try to utilize that when cataloging great items. It also helps with archaeology projects where we find gun parts to know what we are finding to put it into the proper historical context. I feel so lucky that I am able to handle such great pieces of history at work, as well as being able to study the sites that they were used in conflict. It makes history so much more dimensional for me and I hope it does for others when they see our work.

—Madelia Hickman Ring