#Elizabeth #White #Antiques #Arts #Weekly

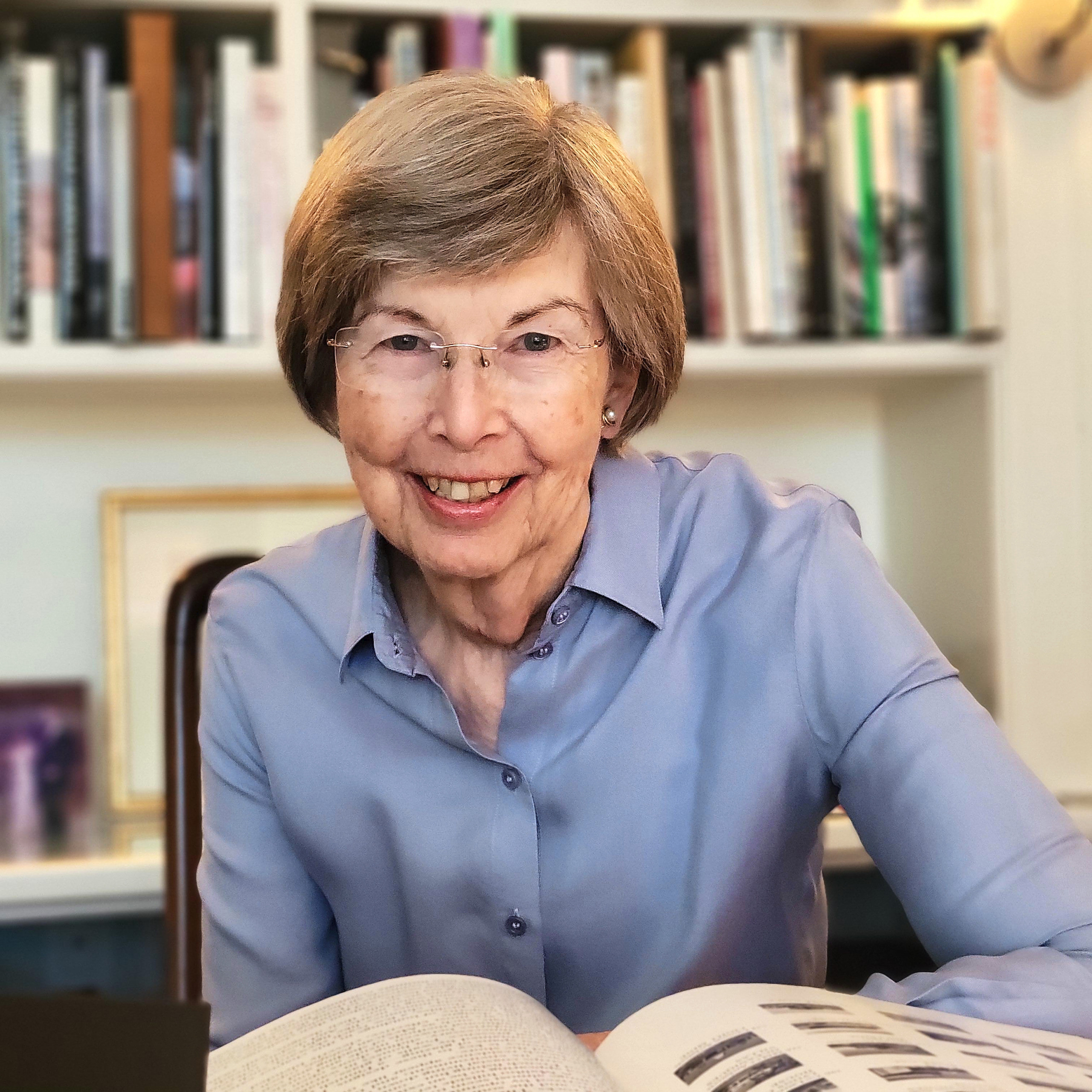

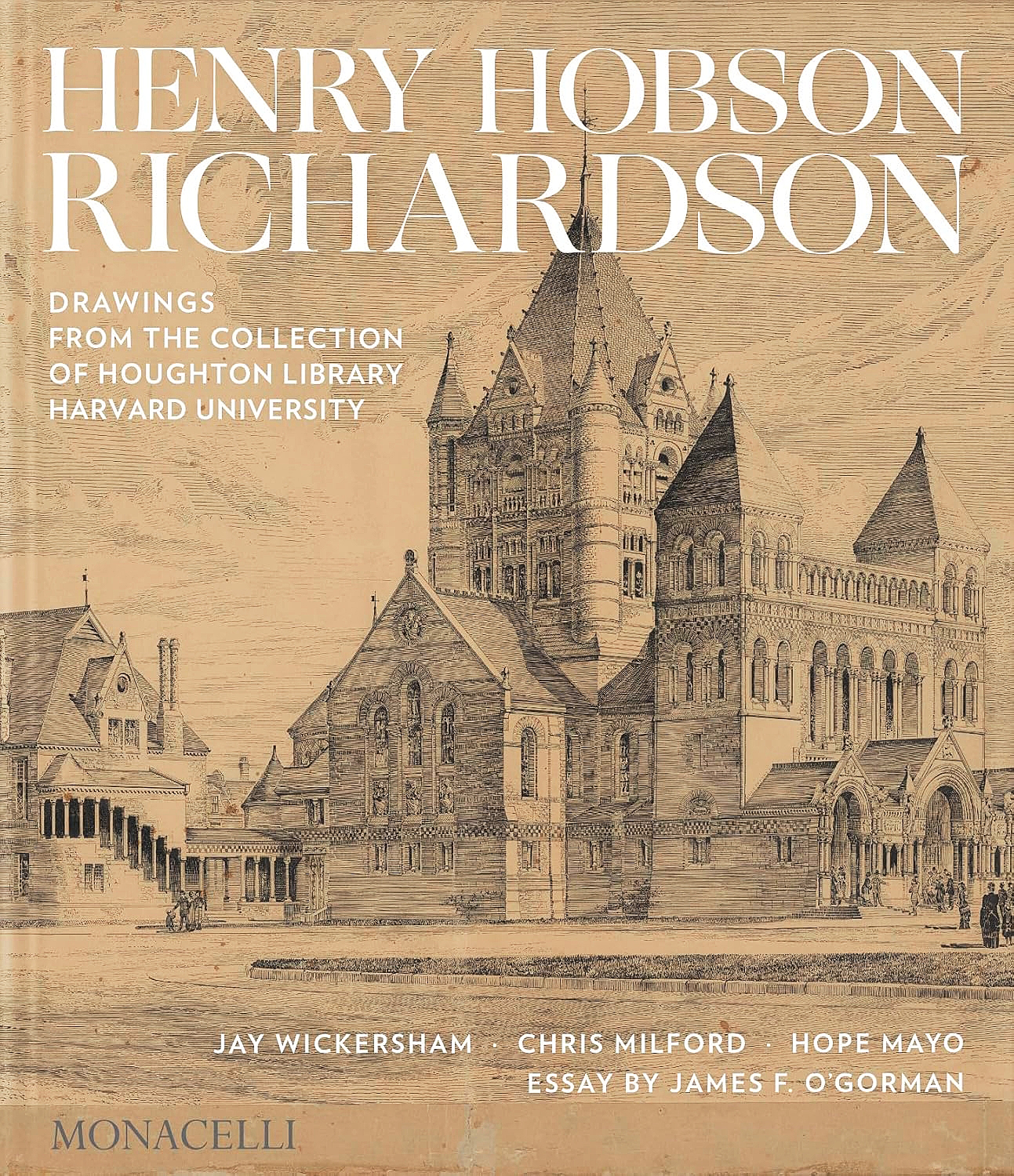

On October 29, Monacelli Press published Henry Hobson Richardson: Drawings from the Collection of Houghton Library, Harvard University, a collaborative effort between authors Jay Wickersham, Chris Milford and Hope Mayo, with support and contributions by James F. O’Gorman and Thomas Hyry. The book is the first in-depth publication of a collection of largely unpublished architectural drawings by Richardson, who is considered one of the greatest American architects of the Nineteenth Century. Antiques and The Arts Weekly touched base with Monicelli’s editor-at-large, Elizabeth White, for more behind-the-scenes details about the inspiration behind the book, the publication process and her personal interest in Richardson’s work.

Congratulations on the publication of Henry Hobson Richardson: Drawings from the Collection of Houghton Library, Harvard University! What inspired this book?

This collection is a treasure trove, an astonishing 4,000 drawings that have been preserved since Richardson’s death in 1886, first by his successors in architectural practice and then since 1942 by Harvard University. Over time, there have been multiple projects to identify and conserve the drawings, with an important exhibition and illustrated catalog by James F. O’Gorman in 1974. This book builds on that work, presenting about 450 drawings that span Richardson’s multifaceted career, documenting the process in his studio and revealing his role and that of the talented younger architects who assisted him.

The project was an extraordinary opportunity for Monacelli, with our focus on design in all its forms but especially on architecture. In essence, the book emerges from a wonderful confluence of curiosity, generosity, professional friendship and determination, especially on the part of the authors, Jay Wickersham, Chris Milford and Hope Mayo, who have examined all the drawings and built a strong framework for studying them.

Both Professor O’Gorman and Thomas A. Hyry, Florence Fearington librarian at Houghton, were exceptionally supportive of the project. Grants from Graham Gund and the Milton B. Glick Publication Fund at Houghton funded the digitization of the drawings, which will make them available to all who are interested, wherever they happen to be in the world.

Can you talk a little bit about how the book is organized?

The book opens with Professor O’Gorman’s essay, which surveys Richardson’s life and career, describing the influence of his training at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts on his practice, the role of important collaborators like Frederick Law Olmsted and the builder Orlando Norcross of Norcross Brothers and his architectural legacy.

Wickersham and Milford focus on the studio, the ways Richardson worked with his assistants and the types of drawings at Houghton, leading into the heart of the book, the drawings themselves. These are presented by project, starting with the sketch and presentation materials and moving through the design development and construction documents.

The book concludes with a discussion of Richardson’s client network, much of which was centered around connections he made at Harvard, and a survey of the materials of the collection and how to access them.

Henry Hobson Richardson: Drawings from the Collection of Houghton Library, Harvard University by Jay Wickersham, Chris Milford and Hope Mayo, with contributions by James F. O’Gorman and Thomas Hyry. The Monacelli Press, New York City, October 2024, pp.336, $85, hardcover.

As editor-at-large at Monacelli, what role (or roles) did you play during the process of the book’s conception and development?

The editor’s role is always to take the material and discover a narrative arc, a path that will allow the reader to navigate easily and draw out essential information. With this book, the reader learns about Richardson himself, the design process and the broad influence of this work, both here in the US, particularly on Frank Lloyd Wright, and internationally. Mayo’s essay positions Richardson very well in terms of the exhibition and publication history, which began immediately after his death with a monograph compiled by the critic Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer at the urging of Frederick Law Olmsted and outlines the ways scholars can approach the material at Harvard.

The editorial and design process is essentially to distill and clarify and to work with the graphic designer — in this case the very talented Jena Sher — to establish a structure for the material with a flow and visual punctuation. With the Richardson drawings, the authors and I agreed on an essentially chronological presentation, and together we decided to create typological groupings and foreground specific projects visually.

The biggest challenge for us was the reproduction of the drawings and conveying the relationship between the line and the support. Sketches are often lightly drawn in pencil while the presentation materials are richly detailed and rendered in black ink, sometimes highlighted with a monochrome or colored ink wash. Color appears sparingly, most often in the construction drawings, where the materials are called out in gray for stone, red for brick and yellow for wood.

Were there any discoveries made about Richardson or his work during the research process?

During their examination of the drawings, the authors were able to assign some “unknown” drawings to specific projects, and they made an in-depth study of the various hands at work in an effort to propose attributions to the younger architects in the firm who are considered Richardson’s principal assistants — Charles Follen McKim, Stanford White, H. Langford Warren, Alexander W. Longfellow, Charles Coolidge, George Shepley and Francis H. Bacon.

Is there a specific aspect of Richardson’s process showcased in the book that you find particularly interesting, and what about it interests you?

I am most drawn to the earliest sketches where Richardson is working out his ideas, and I am particularly fascinated that he did that on such a small scale, even for monumental buildings like Trinity Church. I love seeing the layers — the tentative, light pencil line firmed up gradually and finally inked over so that you can see the whole process on a single page. It’s also revealing to see the marginal notes and calculations. At the other end of the spectrum, my husband and I are inveterate “architourists,” and I always try to see as many buildings as I can while my books are being developed and after they are published. With Richardson, I still have a tantalizing group of buildings to visit, and I am very much looking forward to that.

[Editor’s note: the book is available for purchase at www.phaidon.com/monacelli/architecture]

—Kiersten Busch