#Motel #Memorabilia #Roadside #Lodging #Collectibles #WorthPoint

If you’re a fan of Americana collectibles, you know the span of those items is as vast as America itself. A recent article on collectibles from the American roadside covered fun souvenirs along Route 66, also known as the “mother road.” But travelers also had to find places to stay along the way. Roadside lodging helped build the American travel experience, and motel memorabilia from those early days tells the story of connecting a country.

A PLACE TO REST

When Route 66 opened in the mid-1920s, it was sometimes called an “escape route” for travelers fleeing the Great Depression and searching for opportunities on the West Coast. The early road trippers weren’t just out for an auto adventure—they were heading for a new life.

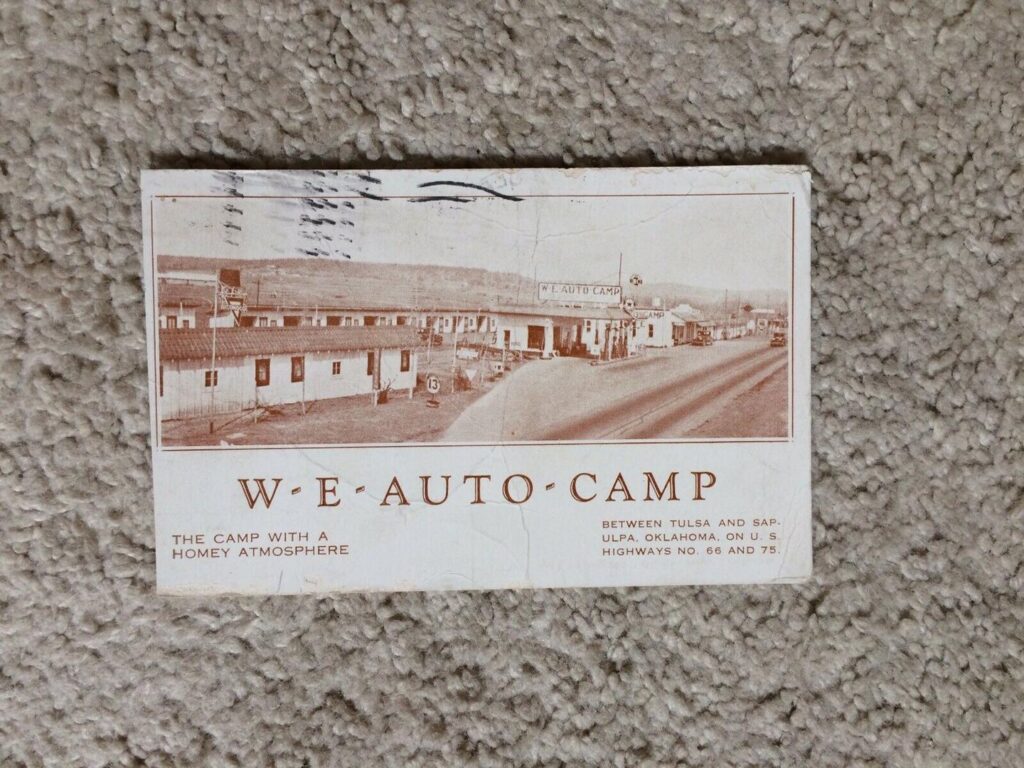

Autocamps popped up first. Sometimes the accommodations were just clean places to pull in, get food, and sleep for the night. Other options were farm fields, where locals along the road allowed cars to pull off to spend the night. Auto camping was decidedly no frills in the early days of the road, so most mementos of this time are postcards and other ephemera.

THE WAR ARRIVES

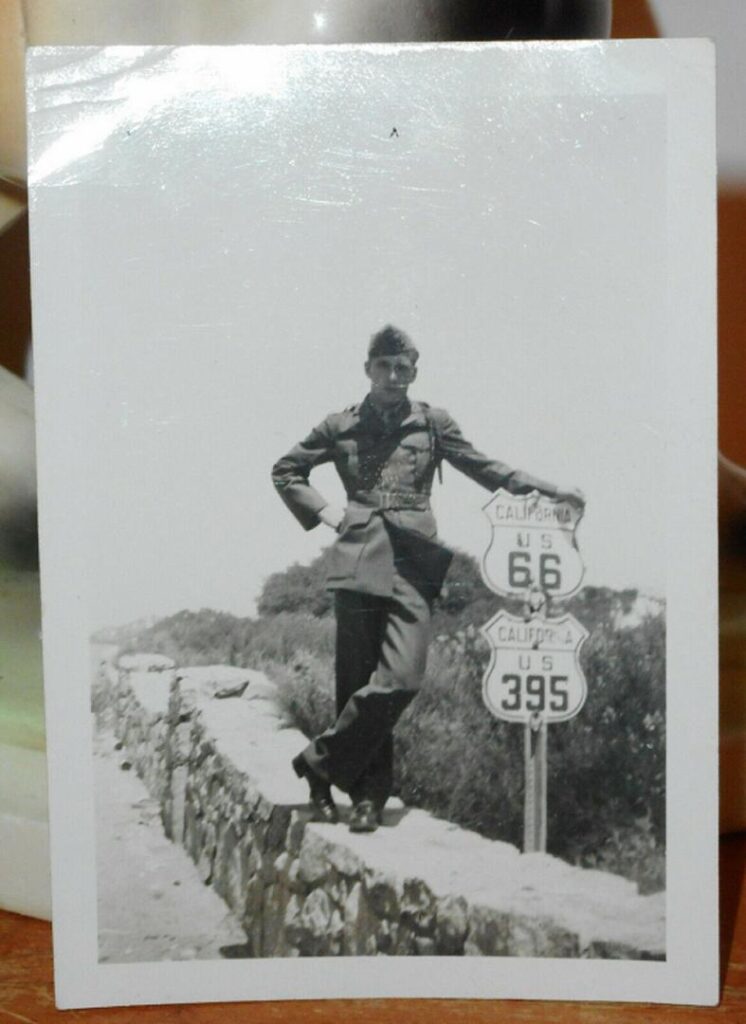

In 1941, when the United States entered World War II, Route 66 became a strategic way for the military to move supplies and troops to new bases. Service members were often assigned to roadside motels and camps for housing while the war effort ramped up. Civilian travelers were often headed to defense plant jobs in Washington, California, and Oregon to build planes and other military machinery.

Fort Sill, Oklahoma, is about eighty-five miles south of Oklahoma City, where Route 66 passes. During the war, it was the training base for the army’s 45th Infantry Division, so thousands of soldiers made their way there. The army used Route 66 as a thoroughfare for supplies and munitions to train the men soon to be deployed overseas. In 1945, it became the training site for the Army Aviation School and the Army Artillery Center, two moves only possible with a decent access road.

JOHNNY COMES DRIVING HOME

When the war ended, men were home again and employed; families were on the move, and with the auto industry booming after the shutdowns for military production, America hit the road hard. While there were hundreds of motels, some would become iconic examples of the American roadside. The Blue Swallow Motel was one of these.

Constructed in 1939 in Tucumcari, New Mexico, the motel is much the same today as it always was, but with modern structural renovations and updates. Arguably, its most famous owner was Lillian Redman, whose husband Floyd purchased it in 1958 as a wedding gift for her. They ran it together until Mr. Redman passed away in 1973. Lillian continued at the motel, often saying, “I end up traveling the highway in my heart with whoever stops here for the night.”

IF YOU FEED THEM, THEY WILL STAY

Many motels along Route 66 started as restaurants or cafes that added rooms for travelers. One of the most famous is the Munger Moss Motel. Owned by Nellie Munger Moss and her husband, Emmitt Moss, it began as the Munger Moss sandwich shop in Devil’s Elbow, Missouri. The couple sold it in 1945, and the new owners kept the name but moved the property to nearby Lebanon, Missouri. They built a café called the “Chicken Shanty” and added the motel.

The motel still operates today, and a grant allowed the owners to restore the large neon sign to its original glory in 2010. This news article states that the owner at the time, Ramona Lehman, even autographed some of the sign’s burned-out lightbulbs for neon fans.

THE INTERSTATE IS BORN

In 1956, President Eisenhower signed the Interstate Highway Act and followed up in 1958 with the Highway Act. The plan was to build a vast system of four (or more) lane highways all over the country, connecting the east and west coasts and crisscrossing as many states as possible.

The highway plans bypassed many rural towns along Route 66, and without enough traffic, many small motels fell into disrepair or closed. Large fast-food and hotel chains took advantage of the new highway locations that would soon bring millions of travelers to their doors.

BIGGER ROADS, BIGGER HOTELS

A significant player in the new roadside landscape was the Holiday Inn chain, begun before the Highway Act but a beneficiary of the new road system. Founder Kemmons Wilson had been on a road trip in 1951 with his wife and five children, and they did not have great experiences in the small towns and motels they encountered.

Wilson’s model was to open hundreds of clean, safe motels for families to enjoy. Linking them under the same chain meant travelers would recognize the name, and the cleanliness and value would be consistent no matter which location a family might choose.

The first Holiday Inn location opened in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1952. In 1994, owners demolished it, but the chain started a new wave of seeing the American road. Holiday Inns caught on fast, but they wouldn’t be the only ones.

THE HOST OF THE HIGHWAYS

Howard Deering Johnson was born in Boston and raised in Quincy, Massachusetts. His career started in 1935 with several drug stores that also had soda fountains and sold ice cream. In 1953, already having the country’s largest ice cream chain, Johnson added motor lodges to some of his locations. Again, the goal was consistency, so travelers would look for “HoJo” locations wherever they went. The orange roofs and tall steeples were beacons to families who knew there would be good food and a clean place to stay.

While the Holiday Inn tag line was “The World’s Innkeeper,” Howard Johnson billed itself as “The Host of the Highways.” The locations often had gift shops selling small souvenirs; some have become very collectible.

Road trips to kitschy motels and attractions might be a thing from the past that only our parents and grandparents enjoyed, but the fact is that these trips helped build America’s tourism industry. From covered wagons to family station wagons, the open road beckoned thousands in search of an adventure or opportunity. Much of the character and charm of roadside accommodations is fading fast, but a few vintage items can bring it all back.

Brenda Kelley Kim lives in the Boston area. She is the author of Sink or Swim: Tales From the Deep End of Everywhere and writes a weekly syndicated column for The Marblehead Weekly News/Essex Media Group. When not writing or walking her snorty pug Penny, she enjoys yard sales, flea markets, and badminton.

WorthPoint—Discover. Value. Preserve.