#Lalique #Glass #Fine #Faux #Jewelry #WorthPoint

One of the most fascinating parts of researching fine and faux jewelry is delving into all the varied materials. It’s easy to just look at a beautiful bauble as the sum of the parts, but when you consider what goes into fabricating each piece of wearable art, it’s like peeling away the layers of the proverbial onion.

For example, when it comes to Lalique jewelry—beginning with René Lalique in the 1800s and continuing with his heirs much later—glass is the building block of many masterpieces. We’ll trace the beginnings of this illustrious French jewelry house, look at some of the things it made early on, and then cover the Lalique items you’re more likely to run across when hitting flea markets and thrift shops in your area.

Lalique Fine Jewelry

First and foremost, René Lalique was a trained artist. After apprenticing with French goldsmith Louis Aucoc in 1876, he attended art school in Paris and London. He learned to sculpt and even did some textile design before beginning in earnest in 1881 as a jewelry designer and fabricator. He sold his work to Aucoc and other big names in Paris, such as Cartier and Boucheron.

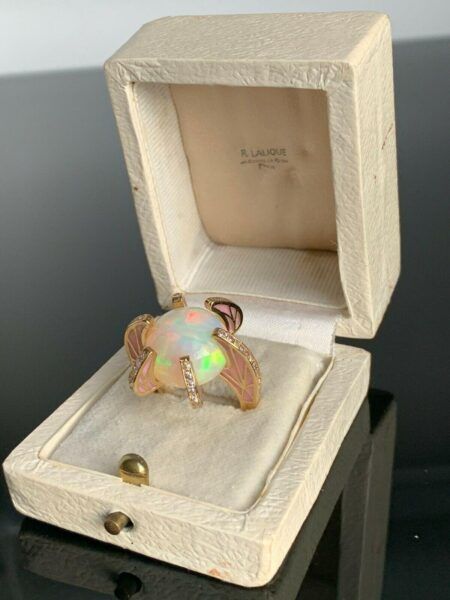

In 1885, he ran his own workshop for a decade, focusing on art nouveau designs featuring the requisite insects, flora, vines, and willowy female figures. He mastered the art of plique-à-jour enameling, a finely crafted glass art, and embellished pieces with natural stones like opals, pearls, moonstones, and tourmaline. Most of these early pieces reside in museums and high-end private collections now.

Eventually, René Lalique’s work turned primarily to glassmaking, and he no longer used gold in his jewelry. His workshop continued to produce some pendants and brooches made of frosted clear and colored glass in the 1920s, but these, too, are seldom found by jewelry hunters today. His business was shuttered by 1940, and he passed away in 1945.

After that, his son Marc carried on the Lalique family tradition of producing glass, including jewelry. The mark on these pieces no longer included “R.” for his father’s name and simply read “Lalique.” Marc Lalique’s daughter, Marie-Claude, took the helm in 1977. In 2008, the business was acquired by a Swiss firm, and four years later, a new line of high jewelry was introduced under the Lalique name. The company is still producing fine jewelry today.

Lalique Costume Jewelry

Technically, the glass pendants and pins René Lalique made in the 1920s qualify as costume jewelry since he did not use precious metals for these settings. But those are so hard to come by, collectors of costume jewelry rarely have a chance to own them. However, because more and more focus went into creating costume jewelry as the decades passed after his death, you have a much better chance of running across those designs.

By the 1970s and ’80s, and well into the 21st century, Lalique produced many different types of costume jewelry items that can be found while thrifting and estate sale shopping today. Clear frosted glass is often associated with Lalique since the company made many objects like vases and perfume bottles using this material. Some styles pay homage to the early art nouveau jewelry made by René Lalique with motifs like winged nymphs gracing pendants or lovely lily of the valley flowers made into earrings and rings using clear frosted glass.

Other colors of frosted glass and colorful polished glass also made their way into jewelry pieces. Good sellers included dome rings and pendants suspended from necklaces made of satin cord. Hearts are some of the more commonly found pendants, and they’re often priced at less than $50, as are the dome rings in an array of colors. Bracelets, on the other hand, whether they’re cuffs or panel styles with multiple glass insets, often sell for hundreds and can be harder to find.

Limited-edition pieces, especially amazing necklaces featuring glass serpents, can also sell for hundreds or even thousands on occasion. Some are still in the original packaging, while others are marked “Lalique” on the plated metal frames, bails, or backings used to hold the glass. The exceptions are the all-glass rings with “Lalique France” etched in script lettering on the backs of the bands.

If items made of frosted glass aren’t marked “Lalique,” be careful attributing them. The name has become a catch-all for many types of frosted glass costume jewelry. One example of a misrepresented item is a frosted glass dove pendant in a gold-plated frame sold by Nina Ricci. These necklaces were sold in packaging reading “Nina Ricci Frosted Crystal Pendant.” Nowhere on the pendant or packaging is the name Lalique mentioned, so it’s doubtful that they’re really made of Lalique glass. It’s probably a situation where the association with bottles made by Lalique to hold L’air Du Temps perfume was linked to these dove necklaces that include generic frosted glass. Once the error occurred, the bad information got copied over and over again.

So, whether you’re buying Lalique jewelry to flip or to wear, look for marks to make sure you’re buying the real deal. You probably won’t be lucky enough to find a René Lalique fine jewelry treasure, but you can certainly snag a piece of fashion jewelry produced while his heirs were overseeing his namesake business. Enjoy those interesting finds instead.

Pamela Siegel is a freelance writer and author who has been educating collectors for more than two decades. In addition to three books on topics relating to antiques and collectibles, she frequently shares her expertise through online writing and articles for print-based publications. Pamela is also the co-founder of Costume Jewelry Collectors Int’l (CJCI) and the proprietor of Chic Antiques by Pamela.

WorthPoint—Discover. Value. Preserve.