#HMS #Bounty #fragment #set #sale #Antique #Collecting

A centuries-old fragment from a ship involved in one of the most notorious events in maritime history – the mutiny on the Bounty – has been discovered in a Rugby in Warwickshire attic.

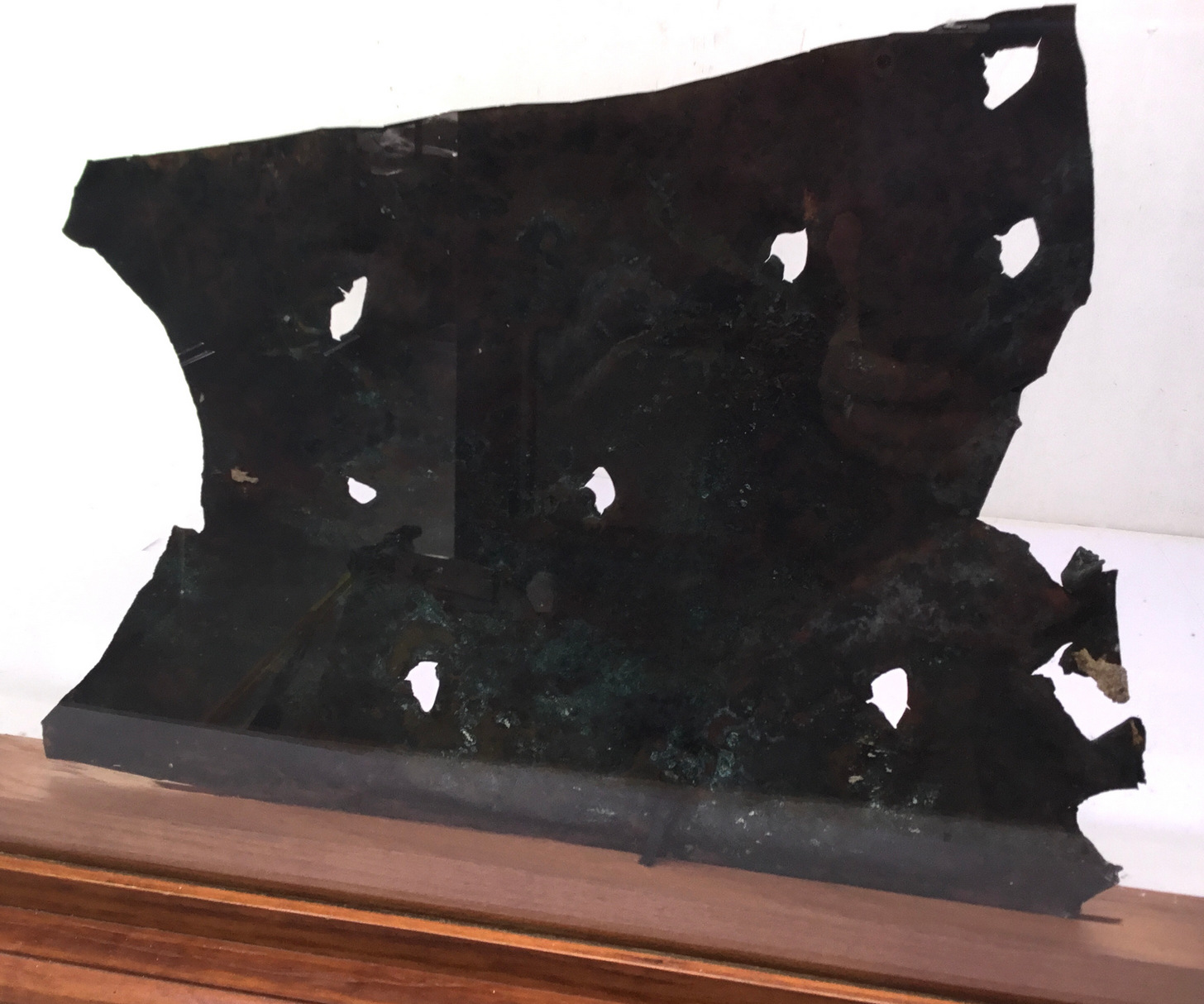

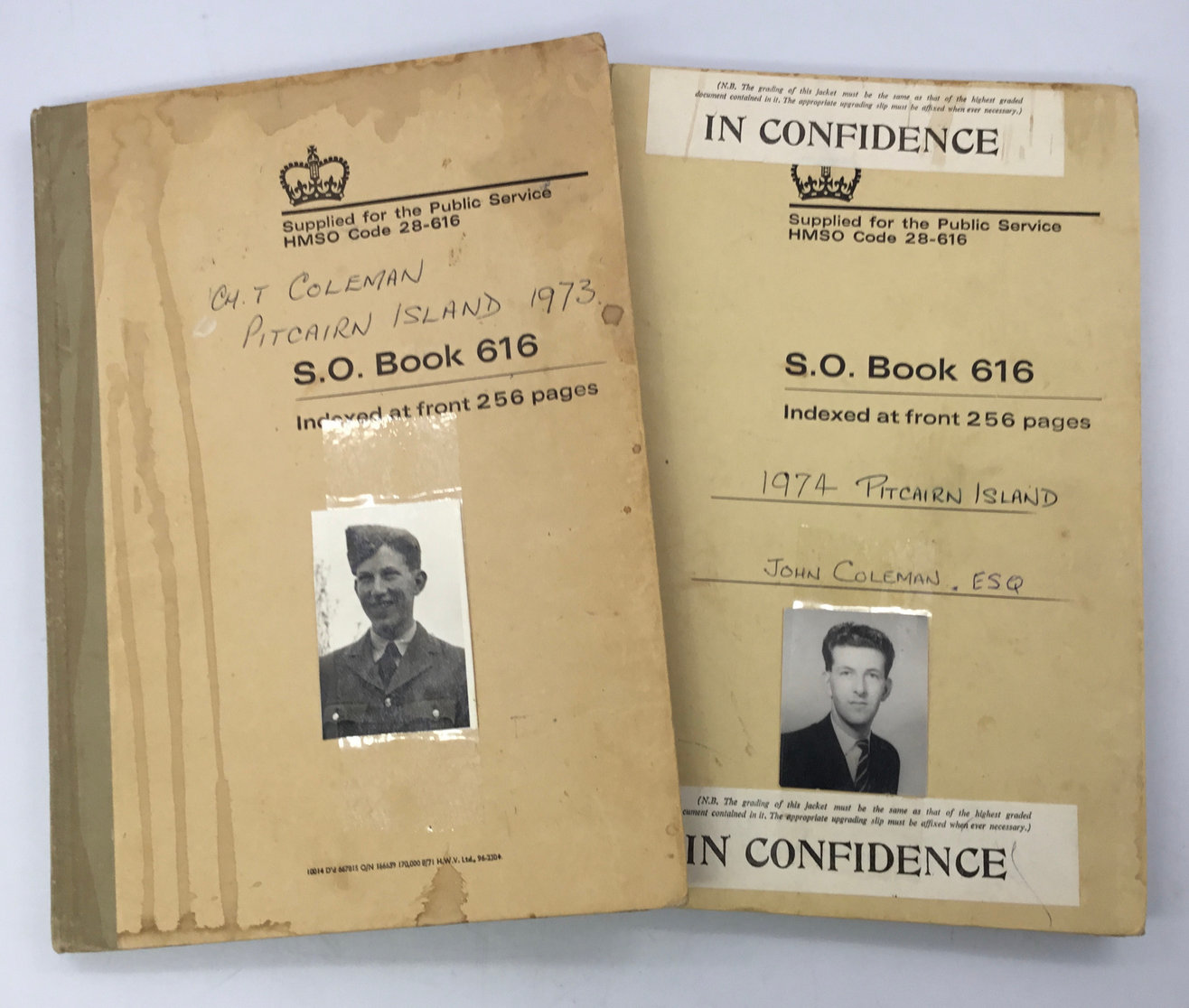

The relic was salvaged from the wreckage of HMS Bounty at Pitcairn Island in 1973 by John Coleman, then a RAF chief technician despatched to Pitcairn from RAF Coningsby in Lincolnshire. During his time at the remote British outpost, he retrieved the large piece of copper sheathing, patinated with verdigris, oxidisation and a patch of barnacles. He brought it back to Engand and proudly displayed it on his mantelpiece for decades.

Bounty was famously burnt by mutineers at Pitcairn in 1790, a story immortalised in films released in 1935, 1962 and 1984. All-star casts included Clarke Gable, Marlon Brando, Mel Gibson and Anthony Hopkins. Now memories of the dramatic events which unfolded 237 years ago are set to reignite at auction. The Bounty artefact will be offered by Hansons Auctioneers on February 26.

The relic has been preserved for 50 years in a bespoke glazed frame. It bears a plaque inscribed, ‘HMS Bounty aka HM Armed Vessel Bounty 1787-1790’. There is also what appears to be an original ship’s nail hammered into the wood to steady it. The fragment is guided at £1,000-£1,500 but its connection to the legendary tale could see it excel, according to Hansons.

John Coleman’s daughter Michelle Childs, a 57-year-old book-keeper from Rugby, said: “I inherited the piece from my late father. He suffered with Alzheimer’s in later life but throughout his illness vividly recalled Pitcairn, his adventures and the friends he made. He used to say Pitcairn was paradise. I believe my father retrieved the piece himself from the seabed in the early 1970s.

“Dad made the casing for it. He was a good carpenter. The relic took pride of place on his mantelpiece for all to see – and begged a question. It was a good conversation starter. Sadly, I lost dad, an Essex boy born in Benfleet, at the age of 87 in 2014.

“For 10 years I kept his historical treasure carefully bubblewrapped in my loft for fear it may get broken or stolen. Now I’ve decided it’s time to part with it to preserve it for future generations. I would love it to go to someone who appreciates Bounty’s incredible story. It deserves to be displayed with pride.”

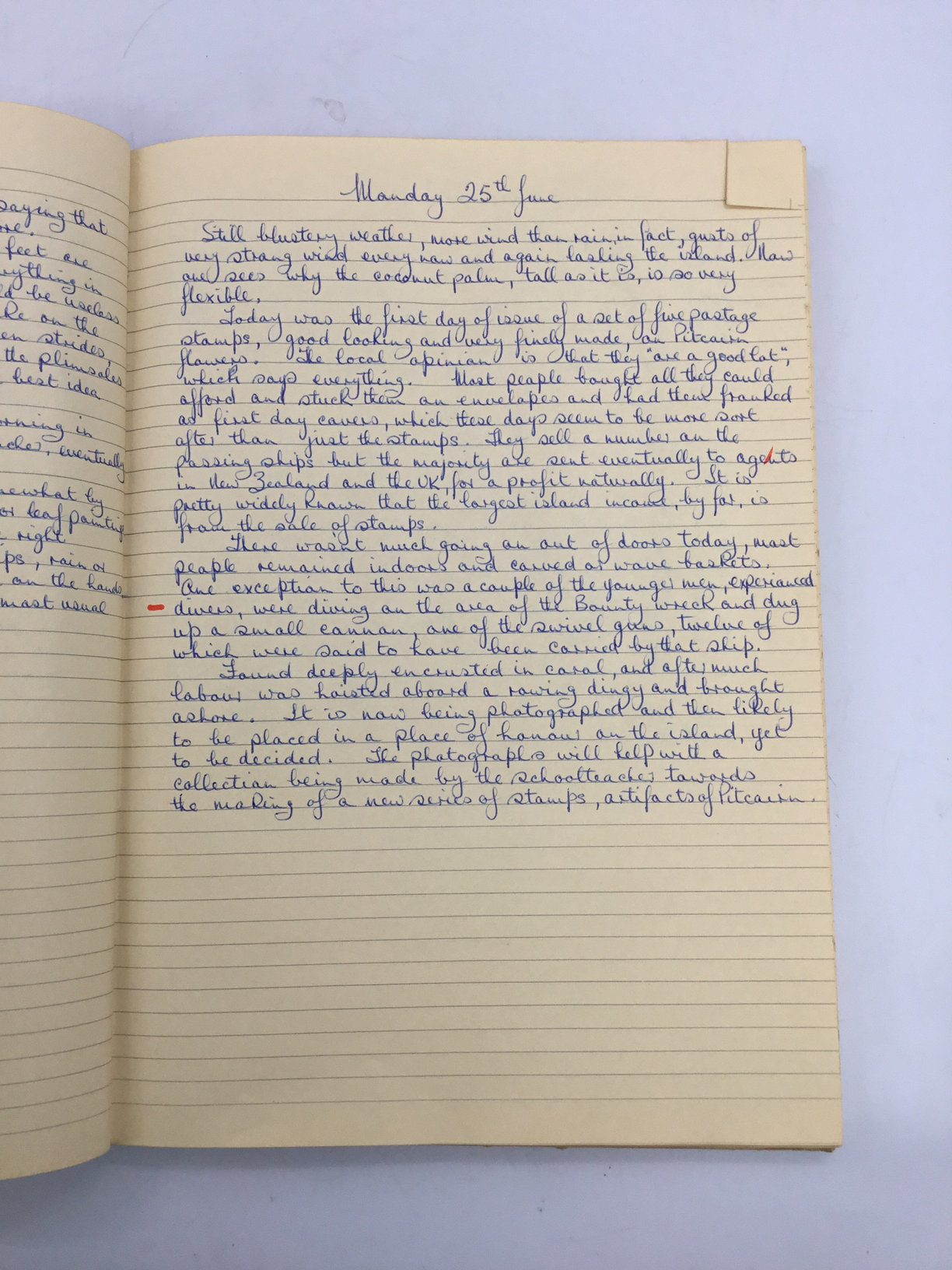

The lot includes Mr Coleman’s handwritten 1973-74 Pitcairn Island logs. While working to set up a radio station on the island, Pitcairn’s history captured his interest. On May 20, 1973, he wrote, ‘You can still see a cannon embedded in the coral, it will probably stay there forever. Nearby there were also sheets of copper from the ship’s bottom, well encrusted with the invading coral’. His July 1, 1973 entry mentions him assisting in raising one of Bounty’s cannons from the seabed.

Matt Crowson, Head of Militaria at Hansons, said: “It’s an astonishing find which travelled 8,940 miles to reach the UK 50 years ago. The mutiny on the Bounty is a legendary story of human endeavour, betrayal, love and adventure. It even has an unresolved mystery. No-one knows how and when leading mutineer Fletcher Christian died. What we do know is that he led a bloodless mutiny aboard Bounty in 1789 and went on to sail to Pitcairn Island where he was among the first Europeans settlers in the Pacific. Christian cast adrift Bounty captain William Bligh and 18 men loyal to him in an open boat with little food and no charts. Somehow they survived a 47-day journey across the Pacific to Timor.”

British merchant ship HMS Bounty was purchased by the Royal Navy in 1787 for £1,950 for a botanical mission. The plan was to sail to the South Pacific island of Tahiti to acquire breadfruit plants for transportation to the British West Indies as a source of food for enslaved plantation workers. However, the mission was never completed due to the 1789 mutiny led by Acting Lieutenant Christian.

In 1787, Bligh (1754 -1817), aged 33, was appointed commanding lieutenant of Bounty. On December 23, 1787 the ship left Spithead, Hampshire, for Tahiti with a crew of 46. Intense storms expanded the journey by 7,000 miles. Eventually, after 10 months at sea, Bounty reached Tahiti on October 26, 1788. The sailors received a warm welcome from natives, lived ashore and embraced Tahitian life. Many obtained native tattoos and Christian married Maimiti, a Tahitian woman.

Five months later on April 4, 1789, Bounty left Tahiti with her breadfruit cargo. However, on April 28 some 22 men joined Christian in mutiny. Bligh was cast adrift in a small boat with 18 men who remained loyal to him. The mutineers sailed to the island of Tubuai but after conflict with natives returned to Tahiti. Sixteen mutineers remained there, taking their chances the Royal Navy would not find them. However, HMS Pandora captured 14 of them.

Meanwhile, Christian, eight crewmen, six Tahitian men, and 11 women, one with a baby, continued on Bounty hoping to elude the Royal Navy. On January 15, 1790 they arrived at Pitcairn Island, which had been misplaced on Royal Navy’s charts. After deciding to settle there, they burned Bounty to avoid detection.

The mutineers remained undetected on Pitcairn until February 1808 when sole surviving mutineer John Adams and some Tahitian women and children were discovered by American sealer Topaz, commanded by Captain Mayhew Folger. Adams and Maimiti said Christian had been murdered. However, Adams later gave conflicting accounts saying Christian [born 1764] had died of natural causes, committed suicide or gone insane.

The HMS Bounty fragment will be offered in Hansons Auctioneers’ February 26 Medals and Militaria Auction.