#Fishley #Pottery #essential #guide #Antique #Collecting

More than 50 pieces of earthenware from a celebrated dynasty of north Devon potters were in demand in a recent sale at Chilcotts Auctioneers and Valuers in Devon. Auctioneer Mary Chilcott explores why collectors love catching some Fishley pottery

More than 50 pieces of earthenware from a celebrated dynasty of north Devon potters were in demand in a recent sale at Chilcotts Auctioneers and Valuers in Devon. Auctioneer Mary Chilcott explores why collectors love catching some Fishley pottery

Collecting Fishley Pottery

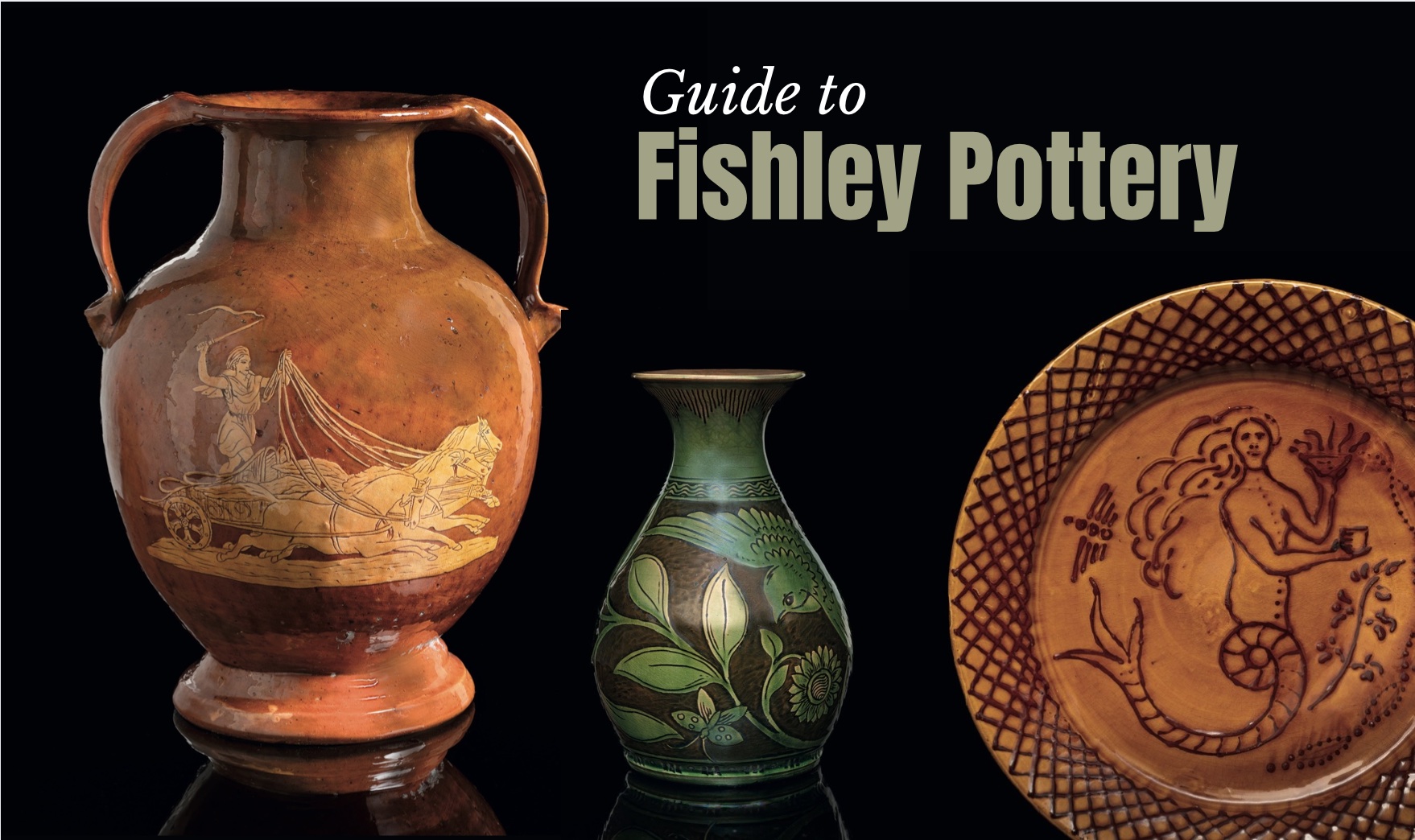

For the collector with a love of region and artisanal skill, nothing presents as enticing a prospect as folk art, and craft pottery in particular. Many dealers and most ceramic collectors will have seen, or handled, the pottery wares marked with the name ‘Fishley’ or its variants.

For years it has graced the market place, quietly collected by enthusiasts who have come to recognise the quality and particular individuality of this ware.

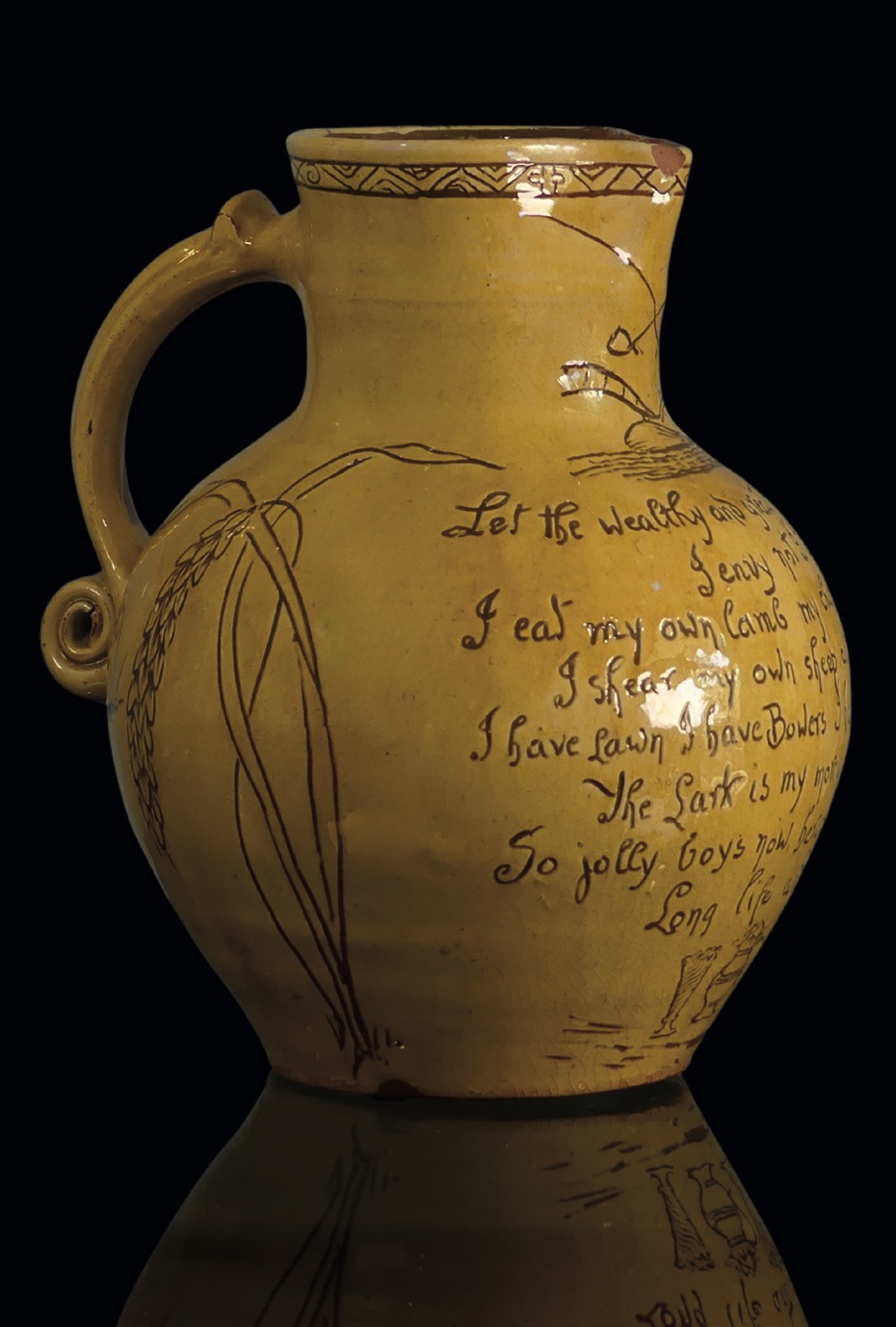

So there was great excitement surrounding our sale of earthenware made by multiple generations of Fishleys at the Fremington pottery. The collection – the largest single collection ever to come to market – included that most iconic Devon piece – a harvest jug, which would have appeared at harvest suppers for the famous county’s cider makers.

Fremington Pottery

Before the Industrial Revolution, when transportation of heavy materials was diffi cult, rural potters needed local resources at their disposal.

With easy access to the Combrew clay beds and the ports at Bideford and Barnstaple, the north Devon region was the perfect spot for such potters to flourish. One family who took advantage of the bounty at hand was the Fishley family.

The first Fishley pottery at Fremington was started by George Fishley (1770–1869), eldest son of the local fish master, who set up a pottery at a local smallholding in Combrew in 1811, leasing clay beds at the nearby Knills Moor.

Best known for his hand-built modelled pieces rather than his earlier, wheel-thrown items, George’s work employed a dark brown ground adorned with white slip, often with sgraffi to, derived from an Italian word meaning “to scratch.” Occasionally he used the method of pressing wet leaves into the slip before burning them off in the firing, which offered a cheaper, quicker method of ornamentation.

Potting was in the family’s DNA, and George’s sons, Edmund (1806-1860) and Robert (1808-1887) both took up the reins, following their father’s innovative use of slip and sgraffi to, and produced highly decorated commemorative and harvest jugs.

Edwin Beer Fishley

Robert was a journeyman potter and soon left to travel the country and, with Edmund’s early death in 1860, the pottery was bequeathed to George’s grandson, Edwin Beer Fishley (1832-1912).

The most well-known of the Fishley potters, Edwin’s work would heavily infl uence the studio pottery movement of the 20th century, particularly the Japanese artist, Shoji Hamada and the father of British studio pottery, Bernard Leach, who referred to Edwin as “the last peasant potter”.

Edwin was involved with the family’s craft from a young age and his artistic fl are soon shone through. He produced new lead glazes which fused more effectively to the local earthenware than glazes used previously, which suffered from fissile flaking.

In fact, Edwin’s glaze was so eff ective that the nearby Barnstaple Art Pottery attempted, but failed, to acquire the recipe.

His early style remained very much aligned with the local tradition, with a fine yellow slip, sgraffi to motifs and lettering. In the late 1860s he began experimenting with cobalt and copper oxides, adding blue and green to Fremington Pottery’s colour palette. These colours were brushed on to otherwise plain designs, used most frequently to highlight floral motifs.

Ethel Mairet

Although Edwin’s decorative pottery flourished, he realised he needed to produce everyday ware to keep the business afloat. So he revived the oval baking dish, decorated inside with a simple, combed effect. One notable admirer of the dishes was Devon-born textile designer, Ethel Mairet (1872-1952), who bought several from Edwin’s stall at Barnstaple’s Pannier Market.

A member of the Cotswold’s craft circle, Mairet’s appreciation caused Edwin to be lauded by major names in the arts and crafts movement. Edwin also continued to promote his pottery at shows throughout the southwest, where his classical Pompeian style became popular.

Noticeably larger than his other work, it required a monumental undertaking of highly-skilled sgraffi to work. In his later years, Edwin returned to the yellow slip, incised decoration style for which the pottery was most well known among collectors.

‘Willie’ Fishley Holland

After Edwin’s death in 1912, the potting baton passed to his grandson, William Fishley Holland (1888-1971), the only member of the family choosing to carry on the tradition.

Edwin’s death put an end to the Fremington Pottery, but the bright-faced William set up just across the estuary in Braunton, building his kiln from scratch.

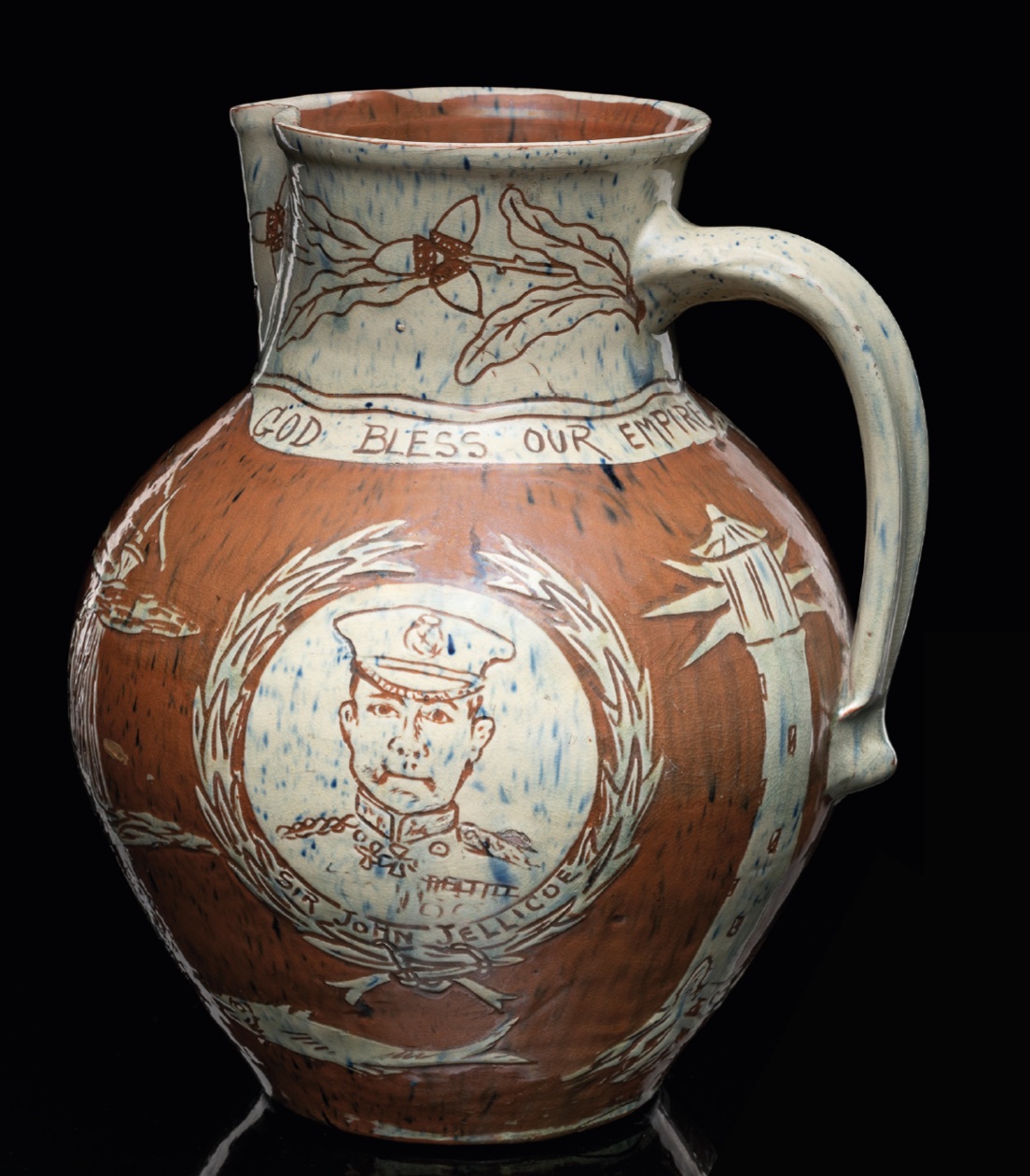

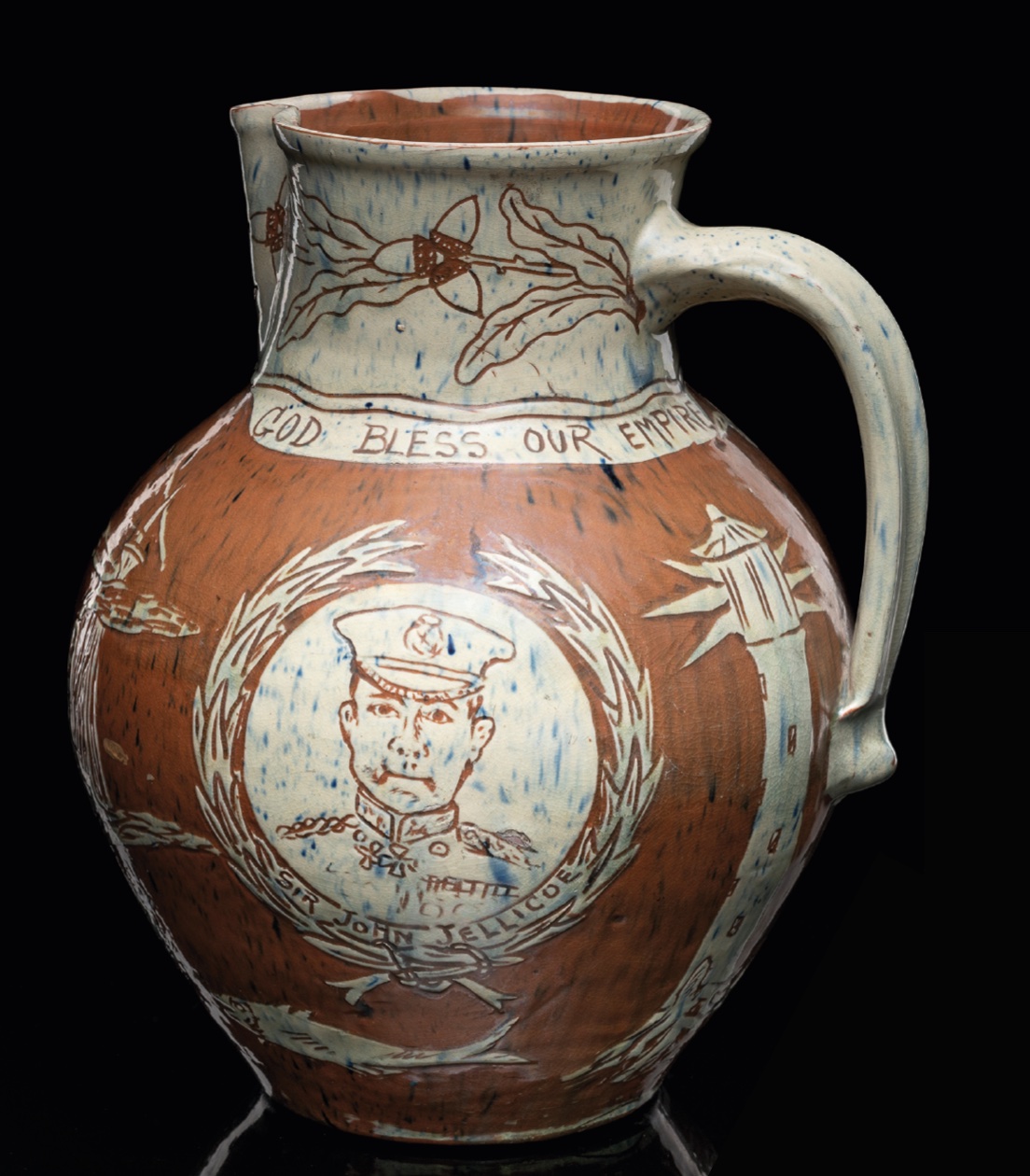

Initially, his products had very intentional Fremington overtones, taking clear inspiration from George Fishley but, with the advent of WWI, and William joining the Royal Flying Corps, Braunton Pottery had to take on new hands.

William agreed to let a young Michael Cardew take throwing lessons from him during family holidays at Saunton, ensuring the survival of the family’s rural pottery legacy by handing skills on to the post-war generation.

Cardew’s later work at Wenford Bridge shows a clear resemblance in terms of sgraffi to techniques, as well as Edwin’s timeless combed slip effect, which Cardew used on his plates. After 1921, William travelled up the coast to Clevedon, Somerset, where he remained until his retirement in the 1960s.

Though the Fishley family no longer makes its wares on the north coast of Devon, there is a handful of potters who are continuing the slipware and sgraffi to traditions, including Harry Juniper, Nick Juniper and Philip Leach.

Scroll handle

Although such motifs were employed nationally, North Devon harvest jugs were distinctive because the potters used a scroll handle, which is coiled where the handle meets the body.

The Fishley family popularised this style even further, taking on commissions and creating pieces for local landowners. George Fishley in particular focussed on patriotic designs, such as celebrating British military boats, while his son, the journeyman potter Robert, transported the North Devon harvest jug concept further afield.

Edwin Beer also continued the tradition, absorbing much of the classic motifs and script but adding a novel twist with his new-found range of colours. Today, the tradition continues primarily through the skilled and exacting hands of Harry Juniper in Bideford.

Harvest jugs

Though the description ‘harvest jugs’ seems to suggest these vessels were used by people working on the land, they were predominantly used in the home at a harvest supper.

While farmers brought their produce to the table, others might take a harvest jug brimming with cider as their contribution.

In North Devon – blessed with the red clay of Combrew and the fi ne white clay at Peters Marland – these jugs were not only utilitarian but also decorative.

A symbol of British folk art, the strong, bulbous forms had a multitude of implicit meanings, including marriages, royalism and patriotism – in addition to wishing the farmer a good harvest. Such messages were expressed in a pictorial language, including blossoming floral motifs symbolic of growing love and fertility.

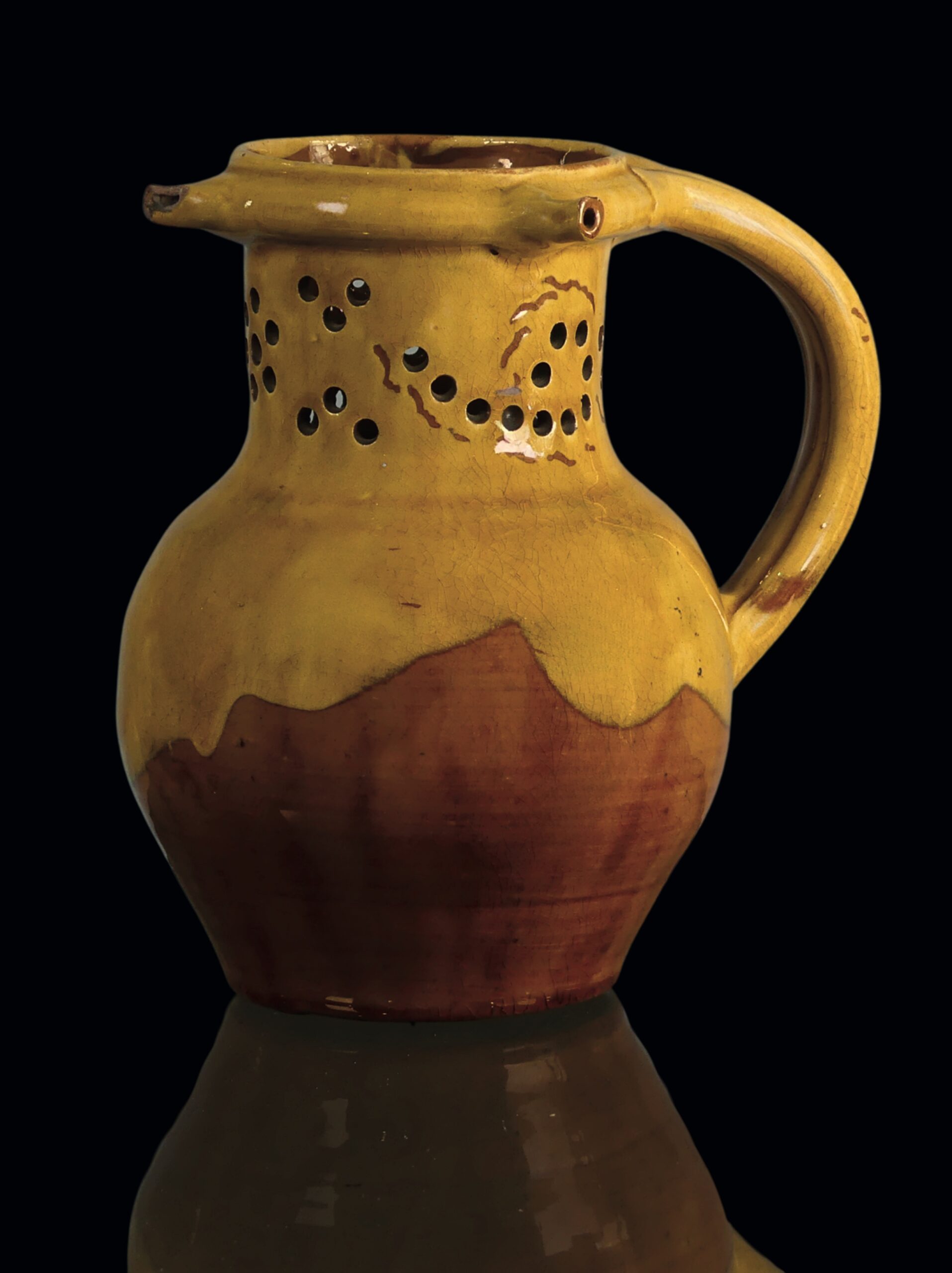

Puzzle jugs

These odd-looking vessels are the pottery equivalent of a joke or a prank. The earliest known example was excavated in Exeter and has been dated to around 1300 AD. It is now part of a fascinating collection at the city’s Royal Albert Memorial Museum.

This complicated vessel (above) is designed to be passed around at merry gatherings; the aim of the game being to drink from it without causing a spill.

It might sound straightforward, but the neck of the jug is usually heavily reticulated and the rim is adorned with spouts.

The level of difficulty afforded by these features resulted in frequent spillages that would have caused much hilarity in the pubs in which they were drinking.

Puzzle jugs were also made in France, where they garnered a global popularity, making them a prudent addition to the repertoire of the Fremington Pottery.

However, due to their complicated design, production of them was never easy to achieve.

The market for Fishley pottery

While some areas of the ceramics market has shown signs of slowing down, the appetite for good quality art pottery is still very much in evidence.

There has also been a robust revival in more naïve style folk art and pottery. Consequently, the market for Fishley pottery is comparatively strong compared to that of, say, Royal Doulton or Coalport.

When buying Fishley wares, as with all ceramics, look for damage and repairs. However, don’t be too ruthless as the glaze didn’t always fuse perfectly with the earthenware, so many examples have small areas where the glaze is flaking.

The work of George Fishley always seems to do particularly well due to its age and influence on wider North Devon pottery. Similarly, Edwin Beer Fishley’s work has a good following, especially his arts and crafts-inspired pieces which are decorated in his signature bold colours.

Spotting Fishley pieces

Fishley pieces are relatively easy to spot once you’ve got your eye in! Look for either bold dark greens with a slightly lustrous edge, or fine yellow or white slip on a red-brown base; even better if it has a well-executed sgraffito scene.

Thankfully, the Fishleys were all very clear when it came to marking their pieces: George Fishley usually impressed G. Fishley Fremington to his works, whereas Edwin and William incised their names to the base along with the location of the pottery.

The Collector

The collection was consigned to Chilcotts auctioneers in Honiton, Devon, by Margaret Squance (née Holland) the great, greatgranddaughter of Edwin Beer Fishley.

Her interest in her family’s heritage was sparked by childhood visits to her great uncle William who was then working out of his Clevedon pottery and gave her miniature pots and jugs.

But it was only when she saw them for sale at a Bristol market that she got the collecting bug. Over the years her passion brought her into contact with renowned contemporary potters as well as ceramics experts from the Antiques Roadshow. She also helped with the writing of the 2008 book, The Fishleys of Fremington by John Edgeler.