#Fairground #art #collectors #guide #Antique #Collecting

Antique Collecting explores some 300 lots of fairground art – the culmination of one man’s 40-year passion – that went under the hammer at Bonhams last year

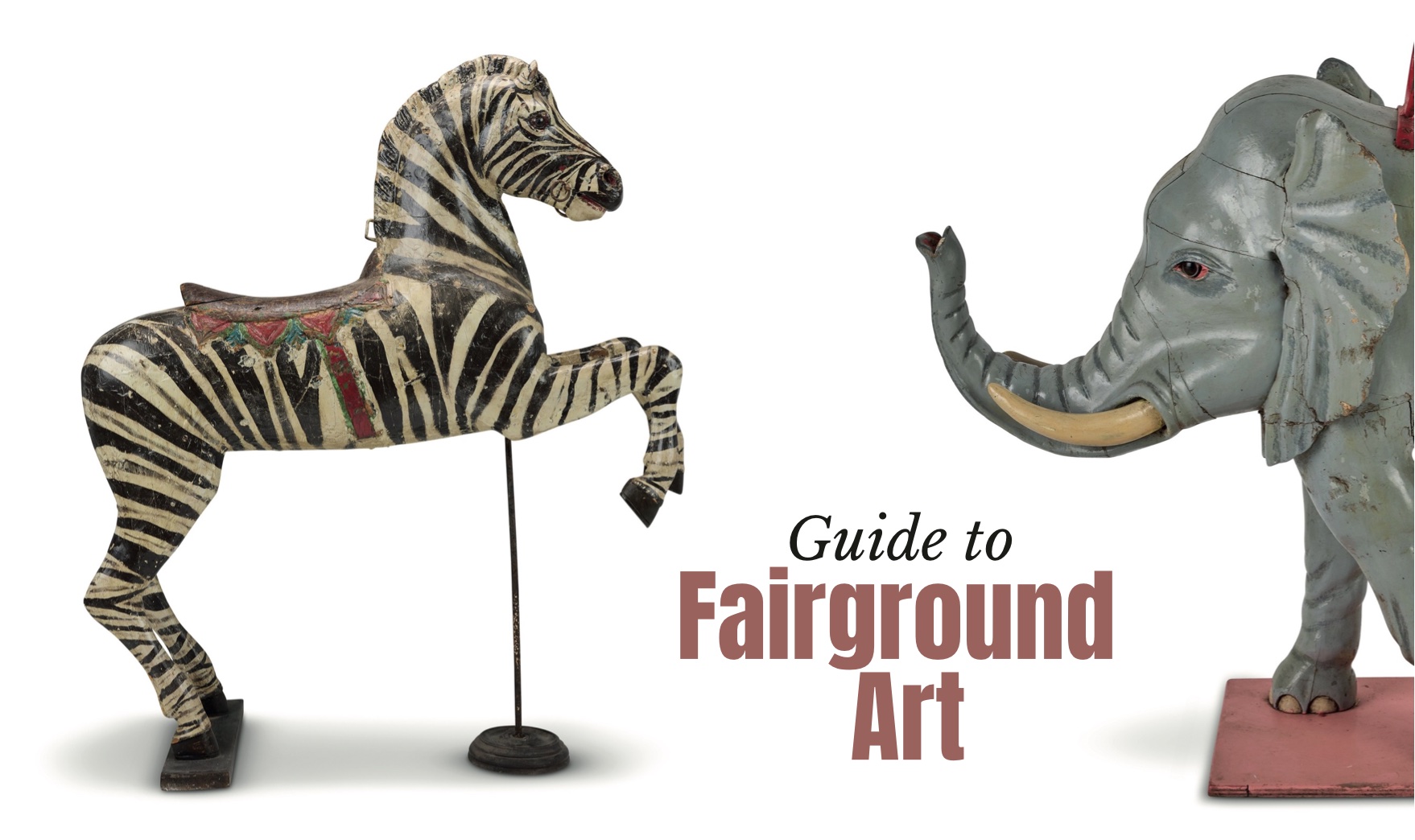

Fairground Art – The Greatest Show on Earth

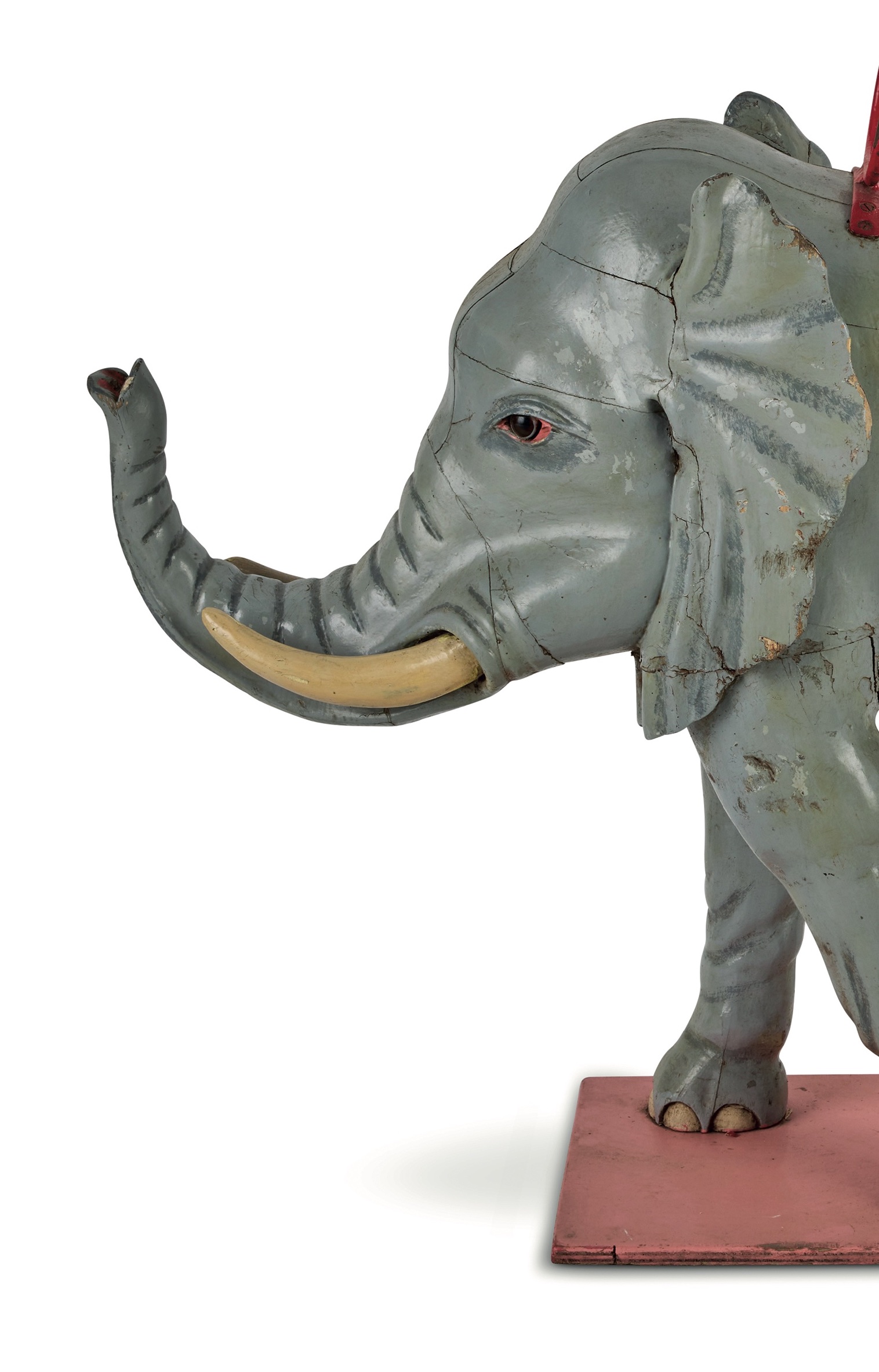

Once a familiar sight, the fairground carousel with its ornately carved wooden animals, has become a rarity. Of necessity, fibreglass animals have replaced the antique originals, and most of the other old rides and shows have all but disappeared.

Fortunately, many examples of decorative fairground work have survived, due to the enthusiasm of far-sighted collectors. One such is Ross Hutchinson whose collection, spanning almost half a century, went under the hammer at Bonhams earlier this year, following a three-week exhibition at the London auctioneer’s New Bond Street saleroom.

Passion for fairground art

Ross’s lifelong passion for fairground art was triggered by a childhood memory. As a young boy he would watch open-mouthed as a procession of trucks hauling the fairground sets made its way into town. For a few magical days the fair captivated the locals, creating memories and changing lives, before packing up and setting off to the next venue.

He was so mesmerised by the fair he went on to become an antiques dealer, with an interest in vintage rocking horses, before establishing a toy museum in Lincoln in 1989, which he ran with his wife. However, his passion for fairground art was never far away and he acquired many of his fairground pieces by “listening to stories, finding leads and receiving tip offs”. His pursuit took him across the world, bringing together items from France and America dating from the early 1900s, and tracing down pieces which capture fairgrounds’ “golden baroque age”.

Fun of the fair

Fairs reached their ultimate splendour around 1900 when people of all ages and from all sectors of society enjoyed the thrills and excitement of the lavishly decorated rides and sideshows. As the expanding railway network made goods cheaply and nationally available, the ancient trading fairs turned to showmanship and public amusement for their survival.

Like the music halls and theatres, fairgrounds were a blaze of opulent colour with decorative detail piled on mouldings and carvings to offer a feast for the senses difficult to find for workers elsewhere in their austere lives. With each ride competing for the money of the fair goers, fairground art reached its peak in the first years of the 20th century.

Edwardians were sociable folk and people of all classes enjoyed strolling out with ostentation apparent in clothes and jewellery. Fairs, music halls, bandstands in the park and even the new department stores all offered public places for lavish display. Each fairground owner and maker of rides strove to make their entertainments ever more splendid, ever more inventive and more lavish.

Collecting Fairground Art

Fairground art has long been appreciated by painters and illustrators and was the inspiration for many mechanical toys during the late 19th century but it was only when the number of fairs declined rapidly after WWII that antique collectors began to take an interest in the artefacts.

By the early ‘60s fairground pieces had become decorators’ accessories and gallopers and sign boards started to be displayed as works of art in smart city homes.

Then, the mecca for anyone looking for striking pieces was “Trad” on the Portobello Road, run by Lord and Lady Bangor – which was stacked high with animal shapes and fairground art.

Buyers were mainly American dealers and collectors who, even then, seemed to prize folk art beyond their British counterparts and had the space to display their purchases.

Growing appreciation

With their appreciation, public awareness grew, and the value of carved figures abandoned in fields and barns increased. Among the eager collectors was Russ Hutchinson, who in 1977, was entranced by the forgotten objects and art on display at London’s Whitechapel Gallery’s exhibition The Fairground.

He said: “Dealers and collectors took interest and started looking for surviving pieces. First to strike me were the signs with their swirling fonts and gaudy colours. Then as a few carved pieces started to appear on the market, I began to really see the quality of the Victorian fairground art, carvings by skilled men working in the tradition of ships’ figureheads, tobacco shop figures and church decoration.

“Most of their work has been destroyed, and their names forgotten, with carvings burnt for the gold leaf finish. It has taken me more than 40 years to gather these baroque survivors together, uniting sets and pairs.”

Spotlight on Frederick Savage

Until recent years, no fairground was complete without its share of Savage-built merry-go-rounds, switchbacks and showmen’s engines.

Each machine was a masterpiece, not only of engineering ingenuity, but also of flamboyant art and craftsmanship. Savages’ fairground machinery was exported all over the world, but the root of this success lay in agricultural implements originally made for local farmers.

The mid-19th century drainage of the Fens by steam power opened up new agricultural opportunities. Savage was quick to exploit these and built and developed carts, hoes and steam threshing machines.

But, ever the entrepreneur, he wanted to conquer new designs and he soon alighted on fairground machinery.

In its 1902 Catalogue for Roundabouts, the company had “patented and placed upon the market all the principal novelties that have delighted the many thousands of pleasure seekers at home and abroad.”

The galloper

Before Savages, and prior to the mid 1860s, roundabouts were driven by young boys or horses pulling round the spinning frame. Similar technology had been applied to horse-driven threshing machines, which Savage was manufacturing at the time. Savage developed a rotating frame on which several animals could be turned abreast. Later he evolved the up-and-down, or galloping, motion.

As the showmen jostled with each other for trade, they required larger, faster and more opulent rides to attract the punters’ attention.

Savage responded not only with Racing Peacocks, Jumping Cats and Flying Pigs as variations on the gallopers theme, but also with the Switchback, the forerunner of most modern rides. Patented in 1888, switchbacks were the most lavish machines ever produced, their cars taking the form of Baroque-style gondalas, gilt-encrusted carriages and newly invented motor-cars.

Mechanisation made the fairground appear modern and futuristic, the latest attractions including ghost shows, cinematograph and x-ray photography.

Maker profile: Andersons

Williams & Anderson was an established Bristol maritime wood carvers founded by John Anderson and his uncles, the Williams brothers. Between them they produced figureheads for sailing ships that filled Bristol’s docks during the 1840s and ‘50s.

But, by the time the demand for wooden ship figureheads died out at the turn of the 20th century, the company had already turned to carved fairground carousel figures.

An article in the National Fairground Archive notes: “Their (Andersons) carved galloper mounts were known for the burgeoning scrollwork under the animal’s belly, complete with Italianate grotesque grins upon its flanks and a flying ribbon frozen onto the neck, lettered with the name of a famous horse or friend.”

Later work went further, with animals heads carved into the body work creating a dream-like, surreal effect.

Other Firms to know

Other British firms such as Lakin and Lang Wheels all became rivals, with German competition becoming very strong in the 1880s, when Fritz Bothmann and Glück of Gotha in Thuringia began producing much cheaper rides, with horses that were carved at the Fredrich Heyn factory in Neustadt. Both he and fellow German maker Carl Müller became known for their dainty prancing horses with gentle faces, although they also carved other menagerie figures.

Fairground Art – What to look for

English carousels are easy to spot because the rides are always turned in an clockwise direction with the most intricate carving seen on the left side of the body. The outside row animals generally bring higher prices because they are larger and more ornately carved. They are also rarer.

Some makers, such as Savage, used metal ears for the horses, as those made in wood needed constant repair.

Valuing Items

The value of a carousel figure is determined by such factors, including rarity, size, ornateness, condition and beauty. The carver responsible for the piece is not always a factor because all the major carvers produced work that was exceptional as well as mediocre.

Some European carousel figures rate highly as being charming – especially Bayol’s rabbits. Beauty may be in the eye of the beholder, with some collectors preferring ornately-carved animals, others may favour a gracefully-arched neck, or an animal in a dramatic pose; while others prefer the sensitive face of a dainty inner-row jumper.

Running repairs

Because the showmen were continually on the move and tended to view the rides as business equipment, rather than art, there was, until recently, few records kept of either the designers or carvers. Added to which, few pieces have the carver’s signature or logo carved into them.

Equally, because the main aim of the showmen was to provide a showy ride at the start of the season, figures and architectural details such as aprons, balustrades and steps were repaired and repainted.

It is because of this continual programme of often poor restoration that any items in virtually original state are now highly prized. Accordingly, a professional restoration can enhance the value of a carousel figure, while a poorly done restoration can detract from it.

The 150-lot sale, The Greatest Show: The Fairground World of Ross Hutchinson, took place at Bonhams New Bond Street in September 2024.