#Dillingers #Stolen #Police #Car #Busting #Jail #Heads #Auction

During the Great Depression, many Americans, nearly helpless against economic forces they didn’t understand, celebrated outlaws who took what they wanted at gunpoint. Of all the notorious criminals, one man, John Dillinger, came to evoke this Gangster Era and stirred mass emotion rarely seen in this country.

Dillinger, whose name once dominated the headlines, was a ruthless crook. According to the FBI, from September 1933 until July 1934, he and his gang terrorized the Midwest, killing 10 men, wounding seven others, robbing banks and police arsenals, and staging three jail breaks—killing a sheriff during one and wounding two guards in another.

And yet, Dillinger became something of a folk hero.

Courtesy Witherell’s Auction

In April 1934 Warner Brothers released a newsreel showing the Division of Investigation manhunt of him. The newsreel showed footage of Dillinger’s father, an elderly farmer, and the residents of Mooresville, Indiana, Dillinger’s hometown. Movie audiences across America cheered when Dillinger’s picture appeared on the screen. They hissed at pictures of D.O.I. special agents.

That Gangster Era returns this month as Witherell’s Auction House presents “The Infamous Dillinger Escape Vehicle,” an online auction featuring the most famous escape vehicle in American history: A 1933 Ford V-8 belonging to Sheriff Lillian Holley stolen by Dillinger in a daring jail escape in March of 1934 that made sensational headlines around the world.

Courtesy Witherell’s Auction

“The Dillinger escape vehicle has been featured in parades and displayed in museums because it is one of the most iconic cars in history,” said Brian Witherell, cofounder of Witherell’s and guest appraiser on PBS’s popular series, “Antiques Roadshow.”

In 1934, Dillinger was behind bars in Crown Point, Indiana, awaiting trial for the alleged murder of a Chicago police officer. Authorities touted the jail as “escape proof” and posted additional guards. According to reports, Dillinger used a fake gun whittled in his cell to corral the guards and take off in Sheriff Holley’s Ford V-8. The car theft was a federal crime and a fatal mistake, causing the FBI to join the manhunt.

Courtesy Witherell’s Auction

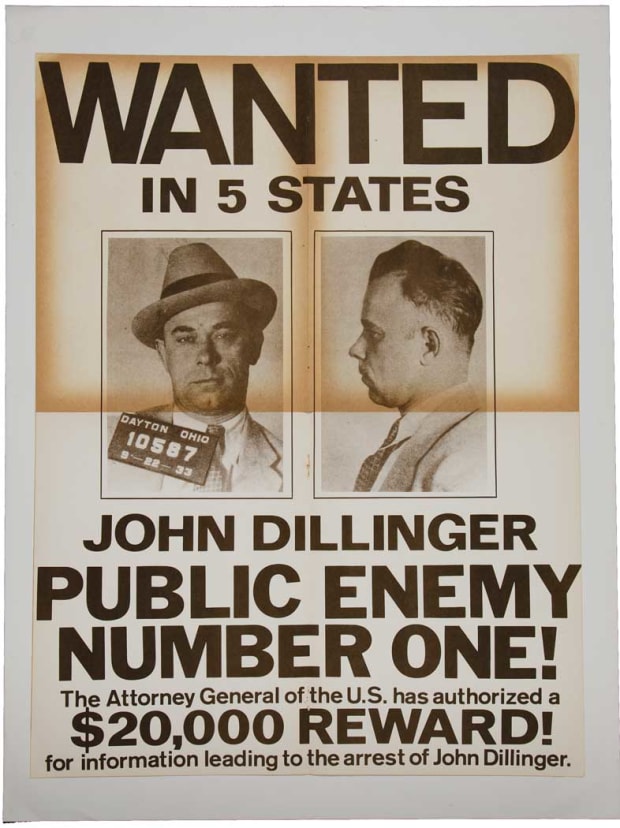

On his 31st birthday, June 22, 1934, Dillinger was declared America’s first Public Enemy Number One. A month later, Dillinger was killed by agents after walking out of a Chicago movie theater.

Auction highlights include:

Courtesy Witherell’s Auction

Courtesy Witherell’s Auction

Courtesy Witherell’s Auction

Bids can be submitted now through Sunday, August 27, at Witherell’s.com. Memorabilia is featured on Annexauctions.com

You May Also Like:

Al Capone Auction Proves Crime Does Pay