#Auctioneer #Robert #Brunk #Appraises #Experiences #Lifetime #Antiques #Arts #Weekly

University of North Carolina Press is publishing A Question of Value: Stories from the Life of an Auctioneer by Robert Brunk in February.

By Laura Beach

A Question of Value: Stories from the Life of an Auctioneer by Robert Brunk. University of North Carolina Press (February 2024), pp. 207, paperback $21, Kindle $11.99.

ASHEVILLE, N.C. — Totems being as old as humankind, the most successful books on collecting probe the psychological bonds we form with objects. Rare triumphs of the genre include Edmund de Waal’s masterpiece The Hare with Amber Eyes and now, much closer to home, A Question of Value: Stories from the Life of an Auctioneer by Robert Brunk, founder of Brunk Auctions. Deeply thoughtful and elegant in its forthright simplicity, A Question of Value is one of the best books on collecting in many years.

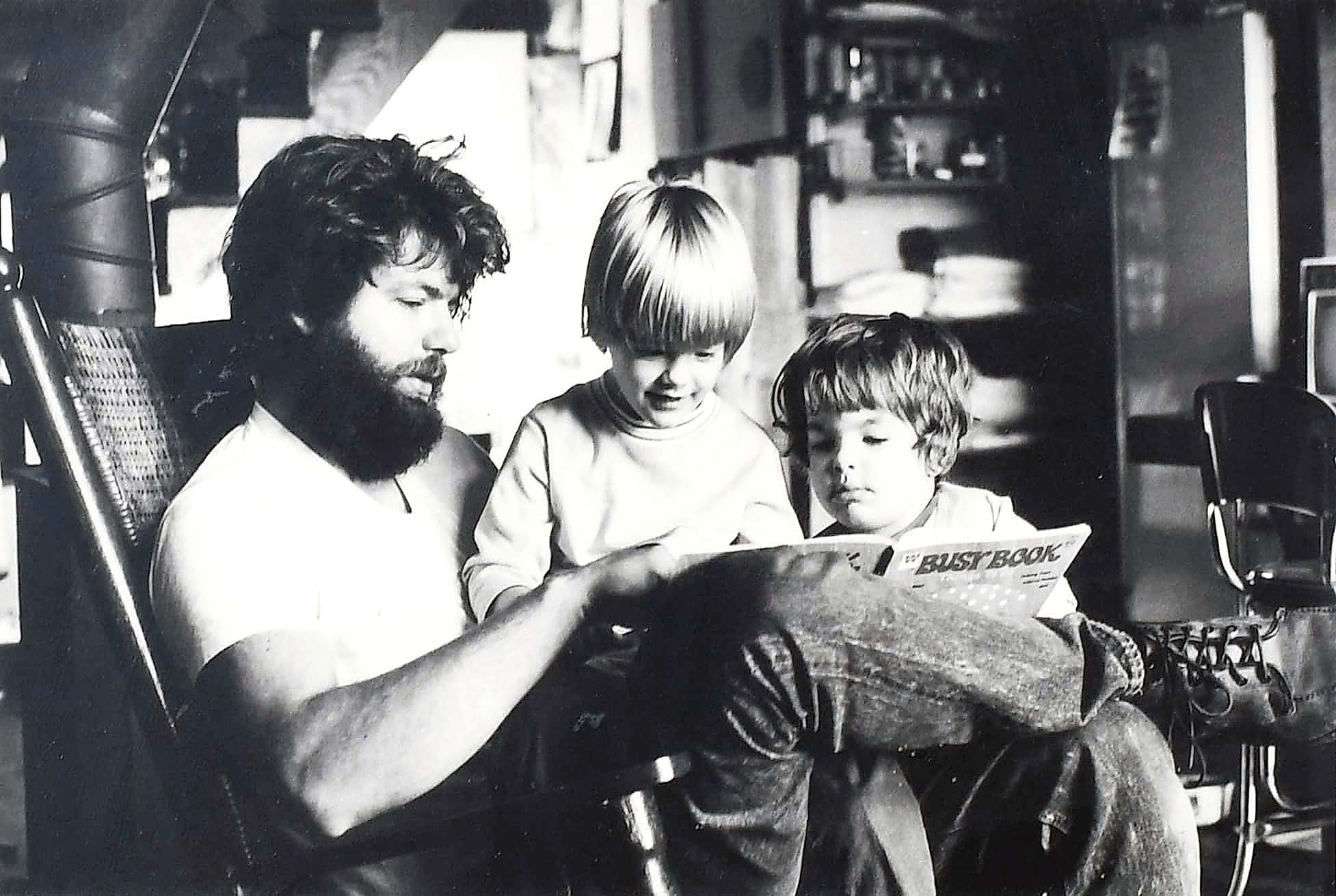

Those who know something about Brunk will not be surprised. From a family of Midwestern Mennonites, the former divinity student sampled a variety of vocations, from teaching to woodworking to farming, before wandering into the antiques business in Asheville, N.C., in the late 1970s. He founded Brunk Auctions — now directed by his son, Andrew, and daughter-in-law, Lauren — in 1983. Framing his life as a series of doorways, Brunk says his reinvention as an auctioneer was at the time “the most recent in a series of restless investigations of what to do with my life.”

Attuned to the visual world, Brunk simultaneously nurtured interests both musical and literary. In the latter realm, he acknowledges the influence of University of Michigan instructor Jeremy Chamberlin, who offered encouragement and edited his work, and describes Michigan’s Bear River Writers’ Conference, where Brunk sojourned for seven seasons. Brunk takes his craft seriously, meeting with friends on Wednesday evenings for readings and criticism. Like Eric Hoffer, the social philosopher whose work as a longshoreman left room to think, Brunk counters the physicality of auctioneering — he “hauled a Victorian sideboard through the August heat, a behemoth few people would want in their home or shop, because it was his work” — with cerebral pursuits. Fascinated with his adopted state, he in 1997 and 2001 published the two-volume anthology May We All Remember Well: A Journal of the History and Cultures of Western North Carolina.

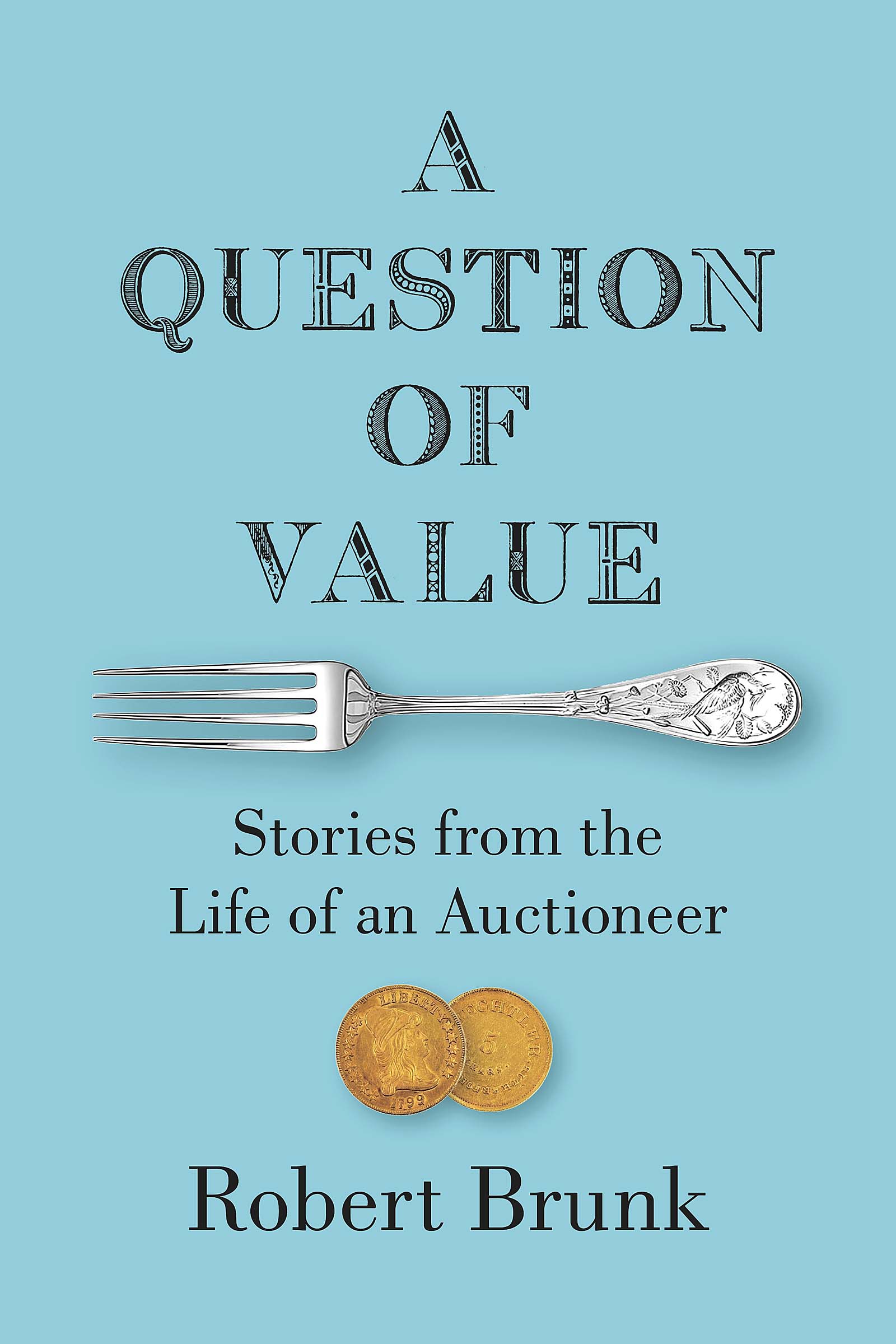

Robert Brunk

Organized chronologically, A Question of Value offers a series of tales, each chapter nominally about an object but more often pondering an encounter or experience, from house call, road trip and appraisal to auction day and charity benefit. In each instance Brunk reflects on meaning beyond mere monetary value and explores his complicated feelings, shaped in part by his Mennonite heritage, about collecting. Of himself, he muses, “Perhaps I was a hunter and gatherer, a student and admirer of regional history and industry, or maybe I wished for my collection to suggest connoisseurship, skill in understanding and evaluating objects. But these personal icons may also have hidden what I was otherwise unable or unwilling to say about myself, messages I am still unable to identify.”

At an appraisal day, he strains to explain the concept of market value to the indignant owner of a damaged pewter tankard. Exasperated by the man’s persistence, Brunk finally tells him, “There is no real value. It is all pretend.” Monetary value is a cultural construct, not intrinsic to the object itself. An avid collector at the start of his career in antiques, Brunk ultimately sells most of what he owns. He writes, “I felt lighter, more flexible, less obligated. If beauty was part of what I was after in assembling these collections, it would now need to be found in other venues. Had these objects been a source of comfort to me, tangible evidence of skill and intent? Had I somehow felt safer with all these things around me? I suffered no feeling of loss after they were gone.”

In a comical chapter on auctioneers’ school, Brunk introduces readers to the stylized intonations of the professional caller. He learns the tricks of the trade — “An old country auctioneer once proudly told me he could get three bids off a slow bidder…” — while yearning to hear the words “trust,” “values” and “accuracy.” He writes, “In the rural South, the auctioneer is part cowboy, farmer, old-fashioned horse trader, con man, and, above all, preacher. The auctioneer’s chant is close to rhythmic Pentecostal preaching, the ‘uh’ after many words: ‘The time-uh for salvation is now-uh.’” An old hand tells him, “You can’t have a decent auction without good bathrooms.”

The Brunk Family, Thanksgiving 2023. Robert Brunk is seated; Lauren Brunk, vice president, and Andrew Brunk, president and chief executive officer of Brunk Auctions, are at left.

Like any good auctioneer, Brunk knows his essential duty is to alert potential bidders to artifacts likely to interest them. Working with consignors requires other skills. Part amateur psychologist and social worker, Brunk develops a talent for listening to people, some of whom are grappling with loneliness or loss. Others are overwhelmed, isolated or lost in mazes of their own design. “Family lore,” even when counterfactual, is its own truth. Objects house memories, Brunk writes, and memories bind individuals to people and places.

Brunk regularly encounters the weird and wonderful, sometimes perilously close to home. In her late eighties, his great aunt Stella cheerfully commissions a gold brooch from the remnants of her discarded dental work. The executor of an estate leads Brunk to a house west of Asheville where an elderly woman left a map indicating the location of coins buried in her backyard, along with instructions for donating proceeds from their sale to the American Communist Party. Brunk obliges. The auctioneer’s recollection of his firm’s appraisal and subsequent sale of the contents of Heritage USA, the site of televangelists Jimmy and Tammy Faye Bakker’s “failed entrepreneurial Christianity,” is a tour de force of social commentary. Brunk writes, “We were witness to the remnants of expansive personal dreams in their worst possible moment, naked, stripped of all pretense, rationale and use.”

If we were to cite but one chapter, it would be “Shingle,” a dazzling account of Brunk’s drive from Asheville to the Tampa area in August 1985 to retrieve the contents of a storage unit, and his exhausted, all but hallucinatory journey home, completed in 22 hours. Dealers and auctioneers are no strangers to extreme travel, but Brunk takes it to another level. Partial to choral music, he fights fatigue by mentally composing a song for three voices, setting his melody to a 1948 poem by Samuel Beckett. “Five hours in, the fat bugs of the night made yellow smears on the windshield as the truck lumbered up I-95 through southern Georgia,” he writes, concluding, “It does not matter that the piece is not performed, because I have it in me. When I read the poem, I hear the tune of it, the music moving with and against Beckett’s words. I easily imagine the whine of truck tires, the muggy air of that night, holding myself up with the steering wheel.”

Robert Brunk reading to his children, Ingrid and Andrew.

Brunk’s writerly final chapter is disconcerting in its unadorned candor. Then 62 and still in good health, he in 2004 responds to an elderly widow’s request for help with downsizing. Her special wish — one he finds impossible to deny, if difficult to fulfill — is that he find a home for her homemade travel videos, a lovingly curated collection documenting the happiest years of her married life. As an experienced estate liquidator, Brunk knows how quickly time drains meaning from family photographs. He muses, “In 300 years, I may be the unknown tenth-generation ancestor of someone. Or does the internet, and other not yet imagined conduits of information and memory, suggest that after death we will all float in a semi-eternal state of being both remembered and forgotten?”

Having long observed the difficulty with which people shed possessions, Brunk asks himself what he would keep in his final years. “Would it be boxes of perfectly shaped stones I had collected on the shingle beaches of Unst; or a folder of music, the pieces I had most enjoyed singing; or a collection of maps with thin green lines, marking places I had explored? Maybe in the end, it would be a box or two of family photos.” Radically, he envisions “…finally letting go of everything: all my possessions, all the relationships, sustaining and fractured, all the unfinished tasks, all the anxious worry over whether I had been truthful and kind, the urgent, the incomplete, the unexplained, and finally even the need to remember.”

Robert Brunk reminds us of another bard of our time, his near contemporary Joni Mitchell. Having looked at our worldly possessions from all sides now, it is their illusions Brunk recalls.